This is the first in a five part series on prayer. You can find all the posts at the following links: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V

INTRODUCTION

In 2012, while teaching an undergraduate honors theology course in Canton, Ohio, I conducted an experiment that would unsettle my students' understanding of contemporary worship. Armed with recording devices, they visited several of the area's largest evangelical churches to document how Scripture was used in worship. What they discovered was sobering. In a typical ninety-minute service, they counted less than half a dozen Bible verses, most offered without context or connection. There were no extended readings, no thoughtful pairing of Old Testament promise with New Testament fulfillment, no responsive readings, no sung psalms. Even in the rare instances where communion was celebrated, it had been reduced to self-service stations with grape juice and crackers, stripped of the biblical words of institution.

The irony was striking. These churches, heirs to a tradition that championed 'sola scriptura,' had largely abandoned the systematic, thorough engagement with Scripture that characterized Reformation worship. One student put it bluntly in her field notes: 'If someone walked in knowing nothing about Christianity, they would learn more about our music preferences than about God's Word.'"

This liturgical drought reflects a deeper crisis in evangelical Christianity that we've been exploring in this series. In the first essay, we examined how contemporary Christians struggle with prayer, often misunderstanding it as a human product rather than divine gift. The second and third essays traced the biblical narrative of communication breakdown—from Eden's intimacy through Babel's confusion—and God's persistent initiative to restore communion with humanity.

Now we arrive at a solution to both crises—prayer as participation in the eternal discourse of the Trinity, mediated through Scripture-saturated liturgy. C.S. Lewis captures this beautifully in Letters to Malcolm when he suggests that Christian prayer is essentially "God speaking to God"—the eternal Son addressing the Father through us by the Spirit. This profound insight cuts against both our natural instincts about prayer and our culture's emphasis on authentic self-expression.

The Book of Common Prayer, standing in stark contrast to contemporary trends, trains us to participate in this divine discourse through its:

Gospel shape—Following the contours of Christ's redemptive work

Thorough grounding in Scripture—Saturating us in God's Word

Biblical Re-narration—Placing us within God's eternal purposes

Before we explore how the Prayer Book mediates our prayers through Scripture, we need to understand three crucial aspects of God's Word. Consider music - not any particular piece, but music as a reality that transcends time and culture. It exists first as pure possibility, as mathematical truth, and as harmony waiting to be discovered. Then in performance, these abstract principles take audible form, becoming something we can hear and experience. Finally, we have written scores through which musicians study, learn, and participate in performing specific works. Although the musical analogy is not perfect, God's Word can similarly be understood through three distinct but interconnected aspects:

First, there's the eternal Word - the divine Logos, "who was in the beginning with God" (John 1:1). Like music in its eternal aspect - transcendent, perfect, and complete - this is Christ in His divine nature, existing before creation as the second person of the Trinity.

Second comes the incarnate Word - "the Word became flesh and dwelt among us" (John 1:14). Like eternal music taking audible form in time and space, we encounter Jesus Christ in history - fully God and fully human, making the divine Word knowable to human ears and hearts.

Finally, we have the written Word - our Scriptures. Like the musical score through which we access and participate in the symphony, these inspired texts allow us to know and join in both the eternal and incarnate Word.

While a musical score enables us to study and participate in music's reality, it doesn't contain or exhaust music's full nature. Similarly, the written Word doesn't contain or exhaust the fullness of the eternal or incarnate Word. Yet as musical notation both reveals truth and enables participation in it, Scripture introduces us to Christ and facilitates our communion with Him. In this sense, the written Word is truly "sacramental" - a necessary means through which we encounter and join in the divine Word.

THE WORD WRITTEN IS SACRAMENTAL

When we understand these three aspects of God's Word—eternal, incarnate, and written—we begin to see why the "post-biblical" trend in contemporary evangelical Christianity represents such a profound loss. As F.X. Durwell observes in his little book The Eucharist: Presence of Christ:

"Holy Scripture is forever linked with that supreme sacrament of Christ's body and the redemption, the Eucharist; the same name is used for both: 'This Chalice,' Our Lord said, 'is the New Testament'; this book also we call the New Testament; chalice and book, each in its own way, contain the New Covenant, the mystery of our redemption in Christ."

This sacramental understanding of Scripture runs deep in Christian tradition. Ignatius of Antioch, writing while being led to martyrdom, found comfort by "taking refuge in the Gospel, as in Jesus' flesh." A few centuries later, Athanasius would declare that "the Lord Himself is in the words of Scripture." Jerome similarly taught that "ignorance of the Scriptures is ignorance of Christ" and that we "feed upon his flesh and drink his blood, not only in the Sacrament, but in the reading of Scripture." This understanding persisted through the centuries, with John Calvin affirming consistently a close connection between the Bible and Holy Spirit. Finally, Thomas Cranmer, architect of the Prayer Book, expressed it thus: "as drink is pleasant to them that be dry, and meat to them that be hungry; so is the reading, hearing, searching and studying of Holy Scripture, to them that are desirous to know God, themselves, and to do his will."

GOSPEL SHAPE

The Prayer Book's eucharistic liturgy provides a powerful antidote to the "post-biblical" tendencies we observed. Just as 2 Corinthians 5:21 declares, "For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God," the liturgy leads us through our fallen condition to Christ's redemptive work and our participation in His righteousness. Consider how this gospel shape unfolds:

Initial Recognition of Need: The service begins with the Collect for Purity and Summary of the Law/Decalogue, revealing both our dependence on grace and the holy standard we fail to meet. The Kyrie/Trisagion voices our need for mercy. Unlike contemporary services that often begin with celebration before establishing our need for grace, this Biblical pattern acknowledges our condition before God.

Praise and Thanksgiving: In response to God's mercy, we join in the Gloria (when appointed), praising God not from our own resources but from the overflow of His prior grace to us. This follows the biblical pattern where praise flows from received mercy: "I will bless the Lord at all times; his praise shall continually be in my mouth... I sought the Lord, and he answered me" (Psalm 34:1,4).

Hearing God's Word: The Ministry of the Word—through readings, psalm, and sermon—proclaims God's saving acts culminating in Christ. "Faith comes by hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ" (Romans 10:17). Unlike the piecemeal Scripture usage we observed in contemporary services, here we encounter substantial readings that connect Old Testament promise with New Testament fulfillment.

Response of Faith: Having heard God's Word, we respond with the Nicene Creed and Prayers of the People, joining the Church's historic confession and Christ's ongoing intercession.

Confession, Absolution, and Comfort: The Holy Spirit uses the proclaimed Word to bring conviction, leading to corporate confession and the assurance of God's forgiveness in absolution. The comfortable Words remind us of God's prior love and work on our behalf. This formal recognition of sin and proclamation of grace is typically absent in contemporary services.

The Peace: Announces the reality of our restored communion with God and each other—another biblical practice largely lost in contemporary evangelicalism.

Participation in Christ's Sacrifice: At the table, we are drawn into Christ's perfect self-offering to the Father. The eucharistic prayer recapitulates the entire history of salvation, weaving together numerous biblical texts into a coherent proclamation of God's saving work.

Communion and Mission: United with Christ through Holy Communion, we are sent out as His body to carry on His mission in the world. This sending forth is grounded in Scripture's pattern of divine blessing leading to mission.

As Ashley Null notes, "Cranmer so wanted BCP worshippers to know the awesome love of God that they would love God more than their own sin." This goal is achieved not through emotional manipulation but through a clear and consistent articulation of the gospel and systematic immersion in God's Word.

Some Anglicans argue that the 2019 BCP has softened the sharp edges of the 1662 BCP’s communication of the gospel, particularly in its treatment of sin and grace. They point to the optional nature of the Decalogue, alternative "comfortable words," and other modifications as evidence of theological drift from the Reformation emphases on sola gratia and sola fide.

Yet, the 2019 Book of Common Prayer clearly preserves the essential emphasis on sin and grace that has marked Anglican worship from its beginnings. We see this throughout, and particularly in the penitential rites, the collects, and the eucharistic prayers. However, we must be careful not to oversimplify the gospel message these liturgies convey. While the movement from sin to forgiveness is central to Christian faith, the Prayer Book's liturgies express a richer theological vision—one that, steeped in Scripture, enables us to respond to God's prior love through the one Word who both enables and mediates our response.

To put this in a different way, the Prayer Book maintains the centrality of Christ's "one oblation of himself once offered" as a "full, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice." But it also shows us that the purpose of forgiveness is our incorporation into God's own life—the gift of God Himself to his people – and it mediates our reception of that gift using the Words of scripture, as I will demonstrate in the remaining sections of this essay.

BIBLICAL SUBSTANCE

“The Book of Common Prayer is 80% biblical quotations and 20% biblical summary." Anglicans have repeated this claim so often it risks becoming a cliché. But in the 19th century, scholars demonstrated its truth. They published detailed studies like The Liturgy Compared with the Bible and The Book of Common Prayer with Marginal References, demonstrating that every line of every liturgy draws from multiple biblical passages.

Let's examine just one example - the Collect for Purity. When we pray these familiar words, we're actually weaving together an intricate tapestry of Scripture:

"Almighty God..." - echoes the heavenly worship of Revelation 19:6 "...to you all hearts are open..." - recalls God's words to Samuel that He "looks on the heart" (1 Samuel 16:7) "...all desires known..." - joins the Psalmist who declared "all my longings lie open before you" (Psalm 38:9) "...and from you no secrets are hid" - draws from Hebrews 4:13, that "no creature is hidden from his sight."

In this single prayer, we've touched four different books of the Bible, spanning both testaments. And this isn't exceptional - it's typical of how the Prayer Book operates.

Consider the Gloria. Its opening line - "Glory to God in the highest and peace to his people on earth" - comes directly from the angels' song in Luke 2:14. But what follows is like a biblical symphony, with every phrase drawing from different parts of Scripture. The address "Lord God, heavenly King, almighty God and Father" echoes Jesus' words in Matthew 11:25, while combining divine titles found throughout Scripture to express both God's transcendent majesty and intimate care. The acknowledgment of Christ as "Lord God, Lamb of God" brings together John's witness to Jesus as "the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world" (John 1:29) with Thomas's confession "My Lord and my God" (John 20:28). When we declare that Christ is "seated at the right hand of the Father," we incorporate both the truth declared in Colossians 3:1 and the royal imagery of Psalm 110:1. The Gloria concludes by recognizing Christ as "the Most High" alongside the Father and Spirit, echoing the triune formula of Matthew 28:19. In this way, a single canticle of praise becomes a comprehensive statement of Christian faith, teaching us to praise God through the very words He has given us in Scripture.

The eucharistic liturgy accomplishes the same thing with particular power. The Sursum Corda's call to "Lift up your hearts" comes from Lamentations 3:41, while its invitation to "give thanks to the Lord our God" echoes Psalm 136. The Sanctus then weaves together heavenly and earthly worship: "Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of power and might, heaven and earth are full of your glory" comes directly from Isaiah's vision of seraphim crying "Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory" (Isaiah 6:3). This cosmic praise then joins with the earthly acclamation "Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest," drawing from both Psalm 118:26 and the Palm Sunday crowds in Matthew 21:9. In this way, our worship is united with both the eternal praise of heaven and the historic recognition of Christ's messianic arrival. The Prayer of Humble Access synthesizes multiple biblical voices into a single prayer of preparation: Daniel's plea "We do not present our pleas before you because of our righteousness, but because of your great mercy" (Daniel 9:18), the Canaanite woman's humble persistence in accepting even "the crumbs under the table" (Matthew 15:27), and the centurion's confession "Lord, I am not worthy to have you come under my roof" (Matthew 8:8). Through such careful synthesis of biblical texts, the Prayer Book trains us to approach God through His own revealed Word.

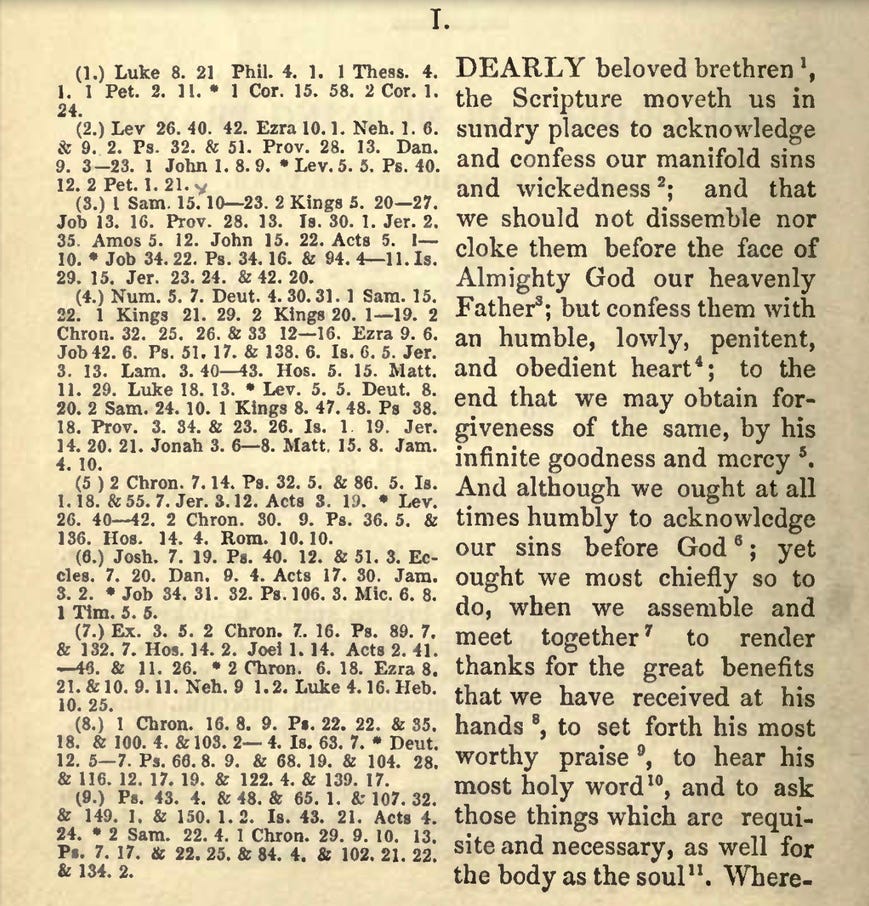

As I mentioned at the beginning of this section, this biblical grounding becomes strikingly apparent when we examine scholarly works that trace these scriptural connections. The image below comes from one such nineteenth-century study titled, The Book of Common Prayer with Marginal References. It demonstrates how even a single page of the Prayer Book draws from hundreds of biblical passages. The right column contains the Prayer Book text, while the left column meticulously catalogues every scriptural reference that informs it. This level of biblical saturation isn't unique to this particular page—it characterizes the entire Prayer Book, making it truly "the Bible arranged for prayer and worship."

THE PRAYERBOOK AS RE-NARRATION

In his work The Discarded Image, C.S. Lewis points to something we've lost in modern times. Medieval Christians, he explains, saw themselves living within an ordered cosmos - a universe vibrant with meaning, hierarchy, and divine purpose. Medieval man, according to Lewis, was a small part of a cosmic, ordered whole - a web of relations from within which, he found his place.

Historically as well as cosmically, medieval man stood at the foot of a stairway; looking up, he felt delight. The backward, like the upward, glance exhilarated him with a majestic spectacle, and humility was rewarded with the pleasures of admiration (C.S. Lewis, The Discarded Image, 185).

Like Boethius and so many others in the Christian tradition, Lewis often used the music as a metaphor to describe both the givenness of God’s good and ordered creation as well as our participation in that order. Consider this reference to the 4th century Christian philosopher, Chalcidius from The Discarded Image:

The native operations of the soul are related to the rhythms and modes. But this relationship fades in the soul because of her union with the body, and therefore the souls of most men are out of tune. The remedy for this is music ; ' not that sort which delights the vulgar . . . but that divine music which never departs from understanding and reason' (C.S. Lewis, The Discarded Image, 55).

Today's Christians often fail to appreciate or consider the implications of the givenness and order of creation. You might say that we are non-cosmological and more likely to see ourselves as isolated individuals generating meaning from within ourselves, rather than as participants in a given reality, God's meaningful creation.

This is where the Prayer Book performs one of its most powerful functions: it re-narrates our story within God's sovereign work of creation and redemption. Consider what happens at every Eucharist. The priest speaks these familiar words:

On the night that he was betrayed, our Lord Jesus Christ took bread...

With that simple phrase, we're no longer just twenty-first century Christians gathered in a contemporary building. We're standing in the upper room with the disciples. The Greek word for this - anamnesis ("remembrance") - means more than just recalling a past event. We're being grafted into the holy history of Israel. Those ancient sacrifices, now fulfilled in Jesus, were offered for us too. We're not just remembering; we're participating.

The baptismal liturgy makes this even more explicit. Listen to how the prayer over the water connects us to God's saving acts throughout history:

We thank you, Almighty God, for the gift of water. Over it the Holy Spirit moved in the beginning of creation. Through it you led the children of Israel out of their bondage in Egypt into the land of promise. In it your Son Jesus received the baptism of John...

Each phrase draws us deeper into Israel's history until we recognize that this is now our history. We’ve been grafted in:

We thank you, Father, for the water of Baptism. In it we are buried with Christ in his death. By it we share in his resurrection.

This pattern of re-narration, or what we might call “cosmological re-contextualization” reaches its climax during Holy Week.

Palm Sunday begins with a stark choice. Waving palm branches, the liturgy connects the church directly to that first Holy Week: "Dear brothers and sisters, from the beginning of Lent until now we have been preparing our hearts... Today, with the whole Church, we herald the beginning of the Paschal Mystery." Then comes the moment of truth. The same congregation that shouts "Hosanna!" will soon hear themselves in the crowd crying "Crucify him!" The liturgy confronts us with our own spiritual fickleness. Yet even here, hope breaks through in the collect:

"Almighty and everlasting God, in your tender love for us you sent your Son... to suffer death upon the Cross, giving us the example of his great humility: Mercifully grant that we may walk in the way of his suffering, and come to share in his resurrection."

Maundy Thursday deepens this pattern. The service marks four pivotal moments, each one drawing us into the upper room:

"This is the night that Christ gathered with his disciples..."

"The night that Christ took a towel and washed their feet..."

"The night that Christ gave us this holy feast..."

"The night that Christ gave himself into the hands of those who would slay him..."

Good Friday brings us to what the Prayer Book calls "the most somber of all days." The service begins in silence - no prelude, no processional, just the weight of divine grief. Isaiah's ancient words suddenly become present: "All we like sheep have gone astray... and the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all." In the Veneration of the Cross, we hear Christ's own lament in the Reproaches: "O my people, what have I done to you? How have I wearied you?"

Then comes the great vigil of Easter. In darkness, a new fire is kindled. A single voice breaks the silence with the ancient Exsultet: "This is the night when Christ broke the bonds of death and hell..." The service moves through salvation history - Creation, Flood, Exodus - until finally, the moment arrives: "Alleluia! Christ is risen!"

The Prayer Book's genius is its comprehensive system for training God's people in restored communication with their creator. If prayer is the communicative dimension of our restored relationship with God in Christ, then the Prayer Book is a potent means of grace. The beauty of its liturgies is that they invite us to pray God's own words back to Him. Yes – the liturgies of the Prayer Book state the gospel clearly – we are sinners deserving death, and by the grace and mercy of God, we are saved. But the Prayer Book goes further and mediates our grateful response to God by God's own Word. Again, this is what Lewis meant when he wrote that, in Christian prayer, “God speaks to God.”

The Word of God grounds every level of Prayer Book worship, from brief collects to the daily office, eucharistic liturgies, pastoral rites and more. Through immersion in scripture, the Prayer Book demonstrates how thoroughly the gospel transforms every aspect of life, teaching us to see and speak to God through His own revealed Word.

In every prayer and rite, we are taught to address God as sovereign Creator while acknowledging our place as creatures. The liturgies consistently recognize Christ's saving, mediatorial role and assume the reality of heaven intersecting with earth. Most importantly, they place our individual prayers within God's larger purposes, training us to see our lives as part of His supernatural work of redemption.

PRAYER BOOK AS RULE OF FAITH AND LIFE

The Rule of Faith guided the early church in interpreting Scripture according to its true meaning and purpose. Similarly, the Book of Common Prayer guides Anglicans in praying according to Scripture's true pattern and scope, helping us see both prayer and reality properly oriented toward and participating in the eternal purposes of God.

Think about how radically this challenges our modern instincts. In this cultural moment, we are tempted to treat prayer as authentic self-expression - speaking our truth to God. The Prayer Book proposes something far more profound: participating in God's truth speaking to God. It does this by:

Grounding our prayers in objective reality - God's revealed Word

Training us to address God as He has revealed Himself

Reshaping our desires according to His will

Uniting our individual voices with the Church's common prayer

Drawing us into the eternal Word's own dialogue with the Father

The stakes here are higher than just improving our prayer lives. What's at risk is our entire vision of reality. To borrow C.S. Lewis's insight, modern Christians have lost what medieval believers took for granted - the sense of living in an ordered cosmos where everything participates in divine purpose. We've traded this rich vision for what philosopher Charles Taylor calls "the buffered self" - the autonomous individual seeking authentic self-expression.

A CONCLUDING INVITATION

Remember those students in Canton who documented the biblical poverty of contemporary worship? Their discovery points to something deeper than just poor liturgical planning. When Christians worry that their prayers are bouncing off the ceiling or wonder whether God truly listens, they are experiencing what inevitably happens when we lose sight of that ordered cosmos Lewis described.

The Book of Common Prayer offers more than a solution to these struggles - it transforms how we understand prayer itself. When we grasp that prayer is fundamentally "God speaking to God," everything changes. Scripture becomes not just inspiration for prayer but the very means by which we're incorporated into Christ's eternal discourse with the Father.

This insight illuminates the stark difference between expressive individualism and the mimetic approach of the Prayer Book tradition:

The "grace" of common prayer lies not in its beauty or antiquity, but in this: it liberates us from the burden of generating prayer from our own bankrupt resources, since (apart from grace) “there is no health in us.” Instead, the Book of Common Prayer invites us into an eternal discourse that precedes us, shapes us, and carries us beyond ourselves into the life of God. In this way, it doesn't simply solve the problems of prayer we identified at the start—it reframes them entirely, showing that prayer was never meant to be a human achievement but always a divine gift.

This is why the Prayer Book remains such a powerful means of grace for the church. Its biblical saturation, gospel shape, and cosmic vision aren't archaic holdovers but a vital corrective for this age of expressive individualism. Through our incorporation into the Church's Common Prayer, we find what our hearts truly seek - not better techniques for self-expression, but adoption into that eternal conversation where the Spirit gives us the Word to cry "Abba! Father!" (Romans 8:15).