This is the first in a five part series on prayer. You can find all the posts at the following links: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V

INTRODUCTION

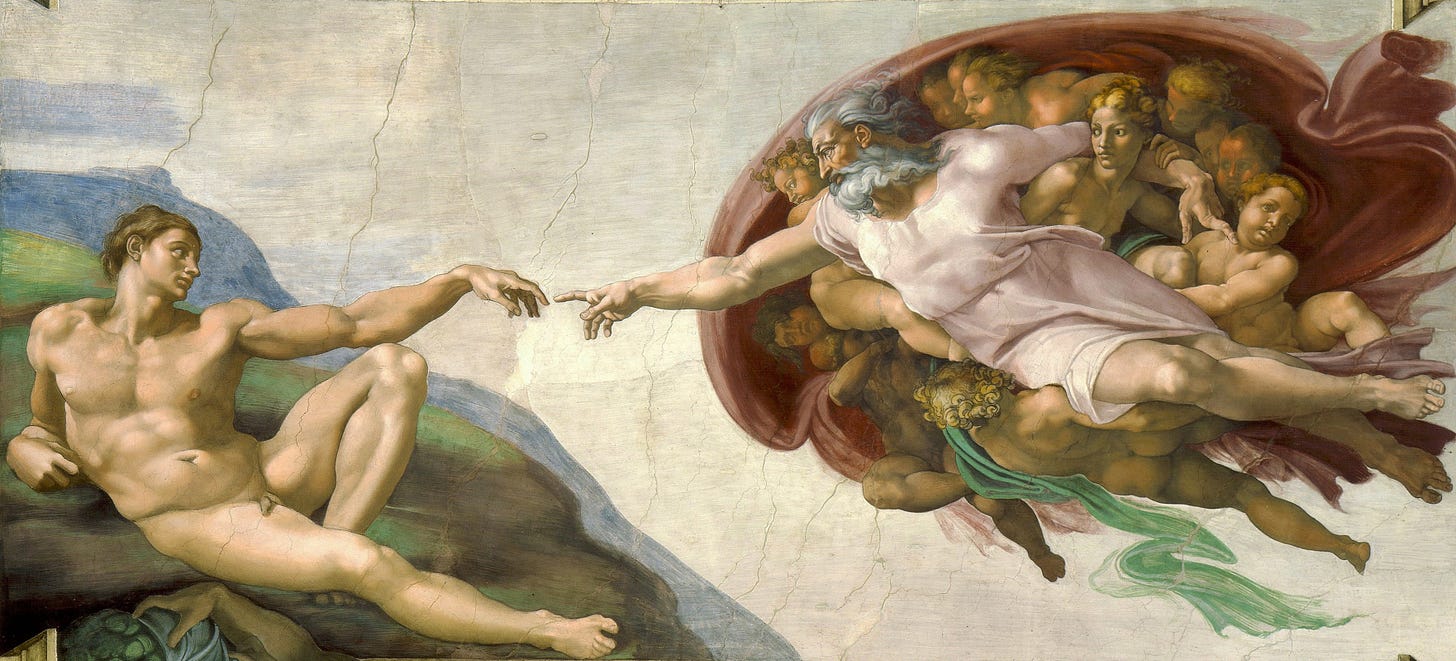

I’ve never walked inside of the Sistine chapel, but I’ve seen pictures of Michelangelo’s masterpiece many times – as I’m sure you have: God reaches out toward Adam, their fingers nearly touching but separated for all time by a short distance. For centuries, viewers have been captivated by this image, and with good reason. In that space between divine and human touch, Michelangelo captured both the glory and the challenge of all human prayer. We were made for this connection – intended to communicate freely with our creator. But our connection, and our communication is broken.

The gap between divine and human communication that Michelangelo captured so powerfully resonates deeply with Christian experience. As we saw in our previous session, frustration and confusion with regard to prayer are commonplace among believers. The student testimonies we examined reveal a striking paradox: though we were created for communion with God, that communion now feels foreign and difficult. We find ourselves in the peculiar position of needing instruction in what should be as natural as breathing.

This difficulty points us toward a crucial theological truth: authentic prayer does not originate with human effort but with divine initiative. Prayer is fundamentally a gift of grace, not a burden we must bear. Throughout salvation history, from creation onward, God has been the one to initiate speech with humankind. Indeed, the entire biblical narrative can be read as God's persistent invitation to restored communication.

The Bible can be rightly understood as one long invitation to prayer.

As we noted in our first session, contemporary approaches to prayer often reflect what C.S. Lewis prophetically identified as a civilization's drift from objective value toward mere subjective preference. When we lose sight of the divine order that precedes and transcends our individual experiences, prayer becomes merely another form of self-expression. But the biblical narrative offers us something far more substantial - an objective pattern of divine-human communication that begins not with our spiritual impulses but with God's creative Word. This pattern provides what Lewis called in The Abolition of Man 'the doctrine of objective value' - not just for ethics, but for prayer itself. Rather than trying to authentically express ourselves to God, we are invited to participate mimetically in a conversation that has been unfolding since before time began.

DEFINING PRAYER

So, what is prayer? The question seems simple enough, but the rich vocabulary of the New Testament suggests otherwise. The Greek text uses several distinct words, each revealing a different facet of divine-human communication. Proseuchomai literally means "to turn toward" God. Deēsis expresses urgent supplication, acknowledging our deep need. Enteuxis suggests the intimate confidence of a child approaching a parent. Eucharistia means thanksgiving, while aitēma represents our specific requests.

Paul weaves three of these terms together in a single verse (Philippians 4:6): "by prayer (proseuche) and supplication (deēsis) with thanksgiving (eucharistia) let your requests (aitēma) be made known to God." The diversity of these terms suggests that prayer means not only "talking to God" but engaging God in a communicative relationship – a complex pattern of turning, yearning, trusting, thanking, and asking. Prayer, in its fullness, is entering into communication with the living God.

Prayer is not the way that we strive to influence God on behalf of ourselves or others. Instead, Prayer is simply responding – in a way fitting for creatures - to the God who has been speaking to us from all eternity.1

Accordingly, if prayer is difficult for us, whether for lack of motivation or because of confusion regarding the outcome, the way to move forward in prayer is first to listen because God has already spoken. Prayer is always a RESPONSE to a WORD already spoken, so to grow in prayer and faith, we start by listening to God.

Think about how a child learns to speak. Long before that first word, babies are immersed in language. Parents speak, sing, and coo over their children for months before expecting any response. Our ability to speak comes from first being spoken to. Although this analogy can be stretched only so far, prayer works in a similar way – we learn to speak to God by first hearing Him speak.

This is why regular church attendance and family devotion are vital for Christians: they immerse us in God’s Word and train our hearts to respond. Church services should steep us in scripture through liturgies, songs, prayers, and sermons, and at home, scripture reading and prayer keep God’s voice present in daily life. As John Calvin observed, 'the Bible is the language of the Holy Spirit,' and by engaging in these practices, we attune ourselves to hear God’s voice speaking all around us—drawing us into conversation, moving us to prayer, and leading us back to Him.

In a future post, I’ll have more to say about the value of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer in helping us to continually “hear…, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest” God’s Word in our church services and at home.

"If you abide in me, and my words abide in you, ask whatever you wish, and it will be done for you" (John 15:7)

GOD SPEAKS FIRST

God speaks creation into being. The Hebrew text of Genesis 1 uses a specific word for God's creative speech - "Vayomer" (וַיֹּאמֶר) - which appears like a drumbeat throughout the chapter. Eight times this phrase "Vayomer Elohim" ("and God said") introduces a new creative act:

"Vayomer Elohim: 'Let there be light'" - and light explodes into being.

"Vayomer Elohim 'Let there be an expanse in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters'" (v.6)

"Vayomer Elohim, 'Let the waters under the heavens be gathered together into one place, and let the dry land appear'" (v.9)

"And God said, 'Let the earth sprout vegetation, plants yielding seed, and fruit trees bearing fruit in which is their seed'" (v.11)

"And God said, 'Let there be lights in the expanse of the heavens to separate the day from the night'" (v.14)

"And God said, 'Let the waters swarm with swarms of living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth'" (v.20)

"And God said, 'Let the earth bring forth living creatures according to their kinds'" (v.24)

"Then God said, 'Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth'" (v.26)

This repeated pattern - God speaks, creation responds - shows us something profound about the nature of God and the power of God’s Word. From the very beginning, God is a God who communicates. His words don't merely describe reality; they create it. Each "Vayomer" marks a moment where God’s speech transforms nothing into something, chaos into order, emptiness into abundance.

Consider what this means - before anything existed, there was God’s Word. Before matter, energy, or time itself - there was communication. This wasn't just God showing off His power; it reveals something essential about who God is. And in the Gospel of John, we discover an even deeper truth: this creative Word that spoke all things into being was not just a what, but a Who. 'In the beginning was the Word,' John declares, deliberately echoing Genesis, 'and the Word was with God, and the Word was God... And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us.'

THE HOLY TRINITY: ETERNAL COMMUNICATION

The Trinity is an eternal communion of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This communion entails communication, as the speaking of God in Genesis 1 and the nature of Jesus as Word suggests. Humans, made in the image of God, are made for communion and communication with God and with one another.

At its heart, this eternal communion is characterized by love. Indeed, when we say "God is love," we're saying something remarkable about communication. Love requires relationship, and relationship requires communication. The Trinity isn't a mathematical puzzle - it's the eternal reality of perfect communion and communication.

THE TRINITY AND HUMAN SPEECH

In his helpful book titled, Prayer and the Knowledge of God, Graeme Goldsworthy reflects on the church's traditional teaching when he writes:

"….the only satisfactory explanation for our human personhood is that it has its source in a personal Creator. If we extend that to the qualities that are distinct to human personhood, we also have to confess that our ability to think, reason and express ourselves creatively stems from our creation in the image of the thinking, reasoning, creative God. The ability we have to speak to each other in human discourse, which reflects thinking, reasoning and creativity, is derived from God in whose image we are made."2

Every time we speak - whether in prayer or ordinary conversation - we're exercising a divine gift, participating in something that reflects God's own nature. This is why the Psalmist writes "let the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be acceptable in your sight, O Lord, my rock and my redeemer" (Psalm 19:14). The psalmist understands that human speech is grounded in the deeper reality of God’s Word and has the potential to glorify the God from whom all blessings flow.

SPEAKING WITH GOD IN THE GARDEN

Having established that creation itself is rooted in God's communicative nature, consider the first dialogue between God and humans.

"The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to work it and keep it. And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, "You may surely eat of every tree of the garden, but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die," (Gen. 2:15-17).

Importantly, God’s words to Adam in Genesis 2 were intimate and instructive, like a parent “teaching a child in the way he should go” (Proverbs 22:6) and warning of potential danger. Also noteworthy is the fact that the serpent enters the scene and begins immediately to sow communicative confusion – “Did God actually say…”?

The disobedience of Adam and Eve was grounded in this communicative confusion and betrayed a breakdown of trust on the part of the woman and the man. Moreover, the first Words spoken by Adam and Eve, in response to God's prior speaking, were words of shame, blame, and dishonesty.

But the Lord God called to the man and said to him, "Where are you?" And he said, "I heard the sound of you in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked, and I hid myself." He said, "Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten of the tree of which I commanded you not to eat?" The man said, "The woman whom you gave to be with me, she gave me fruit of the tree, and I ate." Then the Lord God said to the woman, "What is this that you have done?" The woman said, "The serpent deceived me, and I ate” (Genesis 3:9-13).

Notice that even after their disobedience, God continues to initiate communication. His first words aren't condemnation but a question: "Where are you?" This is crucial for understanding prayer. Even when we hide from God, He seeks us out. Even when we're ashamed, He speaks first.

This biblical account of divine-human communication stands in stark contrast to contemporary expressive individualism. While modern spirituality often begins with the individual's authentic self-expression, the biblical pattern shows us that true prayer is always responsive. Like a child learning to speak in a home rich with family communication, prayer is our participation in a communicative context that precedes us - the eternal, incarnate, and written Word of God. The pattern we've traced from creation through the patriarchs reveals what Lewis lamented losing in The Abolition of Man: an objective order that shapes and guides our spiritual lives. When we understand this, prayer ceases to be a poietic act of self-expression and becomes instead a mimetic participation in the eternal dialogue between Father and Son through the Spirit. Our communication with God is grounded not in our subjective experiences but in the objective reality of His prior Word.

COMMUNICATION BREAKDOWN

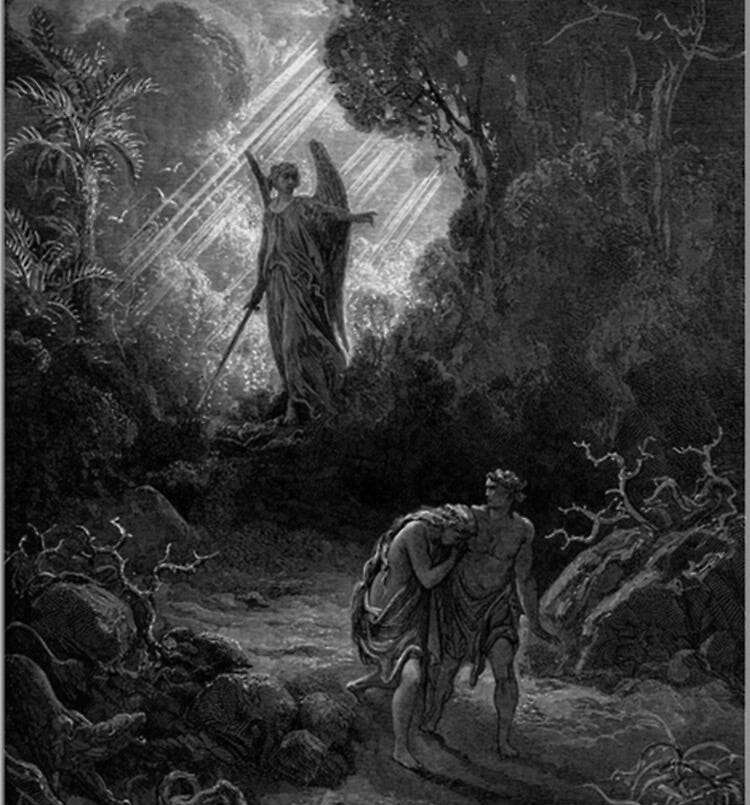

The story that unfolds in Genesis 3-11 reads like a tragic death-spiral - each chapter revealing new depths of broken relationships and failed communication. From Adam and Eve's first act of disobedience, we witness an ever-widening fracture in human relationships with God and each other. Violence in the story of Cain and Able, more violence in the story of Lamech who brags in Genesis 4:24 that “if Cain’s revenge is sevenfold, then Lamech’s is seventy-sevenfold.” After the story of the flood, this breakdown of communion and communication reaches its dramatic climax in the confusion of languages at Babel, where humanity's attempts at self-glorification result in complete communicative chaos.

The consequences of the fall ripple outward in devastating ways. When sin enters the world, the communion Adam and Eve enjoyed with God in the garden is shattered. Cast out from God's presence, they experience for the first time what it means to be spiritually alienated from their Creator. This breach in divine-human communication spreads like a virus, infecting all human relationships with mistrust, blame, and discord.

The effects of sin on human relationships provide a sobering analogue for understanding our alienation from God. When we observe how mistrust, miscommunication, and broken covenant fracture human communities, we glimpse a pale reflection of our severed communion with God. The very gift of language, originally intended as the medium of divine-human fellowship, became instead an instrument of evasion, accusation, and self-justification. What was meant to foster intimacy with God became, in our fallen state, a means of hiding from His presence.

CONCLUSION

Notably, broken communion and fractured communication lie at the heart of our human predicament. But God does not leave us in this state of alienation and confusion. In the next post, I’ll explore how God takes the initiative to restore what was lost. Through the incarnation of Jesus Christ - the Word made flesh - God provides the ultimate answer to our communication breakdown. As we'll see, Christ doesn't just deliver a message from God; He becomes a living bridge, the “one mediator between God and man” (1 Timothy 2:5). In the person of Jesus Christ, true communion and authentic communication with God become possible once again.

As I mentioned in the previous post, prayer is a restoration of the communicative dimension of our communion with God and a fundamental thread in God’s saving work in our lives. I’ll explore this idea in the next post.

This section of my essay is heavily indebted to an excellent book, outlining a biblical theology of prayer. See Goldsworthy, Prayer and the Knowledge of God.

Goldsworthy, 26.

I quite like this line: "The Bible can be rightly understood as one long invitation to prayer." I recall once seeing a (Protestant) seminary advertisement of men sitting in chairs in a library. This is fine and well, as study and discourse must form part of the formation! But, it seems that whenever I see Catholic seminaries advertised, there is oftentimes a seminarian kneeling, or otherwise an ordinance lying (laying?) prostrate. All that to say, I think that your line (above) helps us keep a doxological, amazed gaze at the Bible, keeping us from the ills of arrogance that can sometimes come with study.

Thanks for the comments, Russell. Our class days at Trinity are preceded by morning prayer and followed by evening prayer - Eucharist on Wednesdays, and common meals for faculty, staff, and students daily. For exactly the reason you mention.