Dear Subscriber, in my haste to get this series complete this weekend, my first email went out with a few problems (a repeated paragraph and a few grammatical errors). Please read this version, which has been edited with fresh eyes.

This is the final essay in a four part series titled, “Ordo Amoris: Heartbeat of the Anglican Way.” You can find the previous essays at the following links:

Introduction

As I wrap us this series on the centrality of right desire in the Anglican tradition, it's worth considering how this principle might contribute to our understanding of Anglicanism's past, present, and potential future. First, I’ll offer a few comments about the role of the Homilies and the 39 Articles in ordering right desire according to the reformed emphasis on the gospel of salvation by grace through faith. The point is that all of the Anglican Formularies – not only the prayerbook – are concerned with the right ordering of love.

Next, I’ll turn to a discussion of the importance of right desire for the present and future of Anglicanism. Anglicanism has been described as an excellent way to be a mere Christian, and I believe that this is true. With its emphasis on the right ordering of human affections, Anglicanism has, I will argue, the resources to find unity in the midst of internal strife and provide a compelling witness to an increasingly secular culture. This essay will follow the outline below:

Right Desire beyond the Prayer Book: Examining how the Homilies and 39 Articles align with the reformed emphasis on salvation by grace through faith, and how they contribute to the Anglican approach to ordering human affections.

Right Desire amid Anglican Divisions: Considering how this principle might serve as one of several bridges across our theological and cultural divides.

Right Desire in a Post-Christian Society: Reflecting on the potential relevance of this Anglican emphasis in our increasingly diverse and secular world.

Conclusion: The Significance of Right Desire: Considering the role this principle might play in shaping Anglican identity and practice moving forward.

Right Desire beyond the Prayerbook

At the heart of the Anglican Way is a recognition that the human heart is restless and that it find’s its true fulfillment only in communion with God - a communion made possible because God first loved us and gave himself up for us on the cross of Christ. As St. Augustine famously wrote, "You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you." The Anglican tradition takes this universal human condition seriously, offering a way of faith and practice that continually attends to our restless hearts. This emphasis on right desire is woven through our liturgies, articulated in our theology, and embodied in the common life of our local churches. This is the heartbeat and gravitational center of the Anglican Way.

The gospel, in the Anglican understanding, is the good news of God's loving kindness manifested supremely in Jesus Christ. As Article II of the Thirty-Nine Articles states:

"The Son, which is the Word of the Father, begotten from everlasting of the Father, the very and eternal God, and of one substance with the Father, took Man's nature in the womb of the blessed Virgin, of her substance: so that two whole and perfect Natures, that is to say, the Godhead and Manhood, were joined together in one Person, never to be divided, whereof is one Christ, very God, and very Man; who truly suffered, was crucified, dead, and buried, to reconcile his Father to us, and to be a sacrifice, not only for original guilt, but also for all actual sins of men."

The sacrificial love of Christ meets our deepest need and desire. As we recognize this gift and turn to God in repentance, He begins to fulfill our longing, as only He is able. Our desires and affections are reoriented, setting us on a path of transformation amid God’s people gathered and continually centered around his Word. Again, this is the Anglican Way, and it’s an excellent way to be a mere Christian.

The Book of Common Prayer, as the centerpiece of Anglican devotion, keeps us grounded in the Word of God and is designed to continually remind us of God's loving kindness. The prayerbook’s liturgies, prayers, and scriptural readings invite and encourage us to love God and our neighbors as a grateful response to God’s prior love. As Ashley Null has noted, the heart of the Anglican Way is not “right doctrine, but "right desire." The Prayer Book's emphasis on regular confession, the reading and proclamation of God's Word, the celebration of the Eucharist, and much more, all serve to reorient our loves toward their proper end in God.

Among the Anglican formularies,1 the prayerbook has the most direct bearing on the lives of Anglicans. Indeed, we use the Book of Common Prayer every time we gather for prayer and worship. However, its worth noting that the Catechism, the Homilies and the Thirty-Nine Articles have also been designed to ensure that we get the order of love right, never forgetting God’s prior love before all human response to that love.

The Book of Homilies

Before considering the very brief selections below, please note that it is always important to read theological documents with an understanding of their historical context. We read backwards, in other words, noting that important theological documents were written with an eye towards those authoritative texts and figures who came before. Thus, we should read Cranmer understanding both his critique of late medieval penitential practice and his appreciation of the Bible and notable theologians like Augustine. Cranmer, if Ashley Null is correct, understood his own work as correcting recent error in order to put the Church of England back into continuity with biblically faithful traditions from which the late medieval church had departed. Thus, the emphasis, in all the Formularies, on salvation by grace through faith should not be read as an end in itself. Rather, this emphasis is meant to set the older tradition of rightly ordered love back on track. Consider a few brief quotations from the Homilies, which were meant to help form clergy and ensure gospel centered proclamation in English Churches:

From the Homily of Salvation:

"Because all men be sinners and offenders against God, and breakers of his law and commandments, therefore can no man by his own acts, works, & deeds (seem they never so good) be justifyd, and made righteous before God: but every man of necessity is constrained to seek for another righteousness or justification, to be received at Gods own hands, that is to say, the forgiveness of his sins and trespasses, in such things as he hath offended."

Later in the same homily:

"For it is of the free grace and mercie of God, by the meditation of the blood of his Sonne Iesus Christ, without merite or deseruing on our part, that our sins are forgiven us, that we are reconciled and brought again into his favour, and are made heires of his heavenly kingdome."

The Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion

Perhaps more importantly, the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion clarify the theological foundation of the Book of Common Prayer. Although the prayerbook was Cranmer's first project, the articles have served as something like a "rule of faith," ensuring that Anglicans rightly interpret the theology of the prayerbook. The Articles also serve as a guide for all prayerbook translation, revision, and development. They ensure that the mediation of grace in the prayerbook tradition is always rooted in reformation theology.

The theological emphasis found in the Articles provides a clear direction for how the Anglican Way shapes our desires. Article X, "Of Free Will," teaches that humans cannot turn to God by their own power, but only by God's grace working in us. Similarly, Article XII affirms that good works are the fruit of faith, springing from a lively relationship with God but never the grounds for salvation. This deeply reformed theology ensures that the transformation of desire is always a response to God's grace, never an achievement of human effort.

This emphasis on grace and faith is further reinforced in Article XI, "Of the Justification of Man":

"We are accounted righteous before God, only for the merit of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ by Faith, and not for our own works or deservings."

The Articles also help maintain the unity of belief and practice within Anglicanism. Article XIX, "Of the Church," defines the Church as the place where the "pure Word of God is preached" and the sacraments are "duly ministered." This balance between Word and sacrament encapsulates the Anglican vision of how grace reshapes our affections, ensuring that our worship is always grounded in the truth of the gospel.

The reformational character of the Articles is further evident in their treatment of predestination and the exclusivity of salvation through Christ. Article XVII, "Of Predestination and Election," states:

"Predestination to Life is the everlasting purpose of God, whereby (before the foundations of the world were laid) he hath constantly decreed by his counsel secret to us, to deliver from curse and damnation those whom he hath chosen in Christ out of mankind, and to bring them by Christ to everlasting salvation, as vessels made to honour."

This affirmation of divine election aligns with Reformed theology and emphasizes the primacy of God's grace in salvation. Moreover, Article XVIII, "Of obtaining eternal Salvation only by the Name of Christ," firmly rejects any notion of universal salvation apart from faith in Christ:

"They also are to be had accursed that presume to say, That every man shall be saved by the Law or Sect which he professeth, so that he be diligent to frame his life according to that Law, and the light of Nature. For Holy Scripture doth set out unto us only the Name of Jesus Christ, whereby men must be saved."

The Thirty-Nine Articles firmly establish Anglican theology within the Reformation tradition and require all Anglicans to take seriously the idea that the catholic tradition needed reformation theology to develop with integrity. Reformation theology matters greatly, because without it – the tradition of rightly ordered love, found throughout scripture and the whole history of the church – devolves into works righteousness. Accordingly, the Articles reject works-righteousness and affirm the centrality of salvation by grace through faith. They also maintain a Reformed understanding of the sacraments and ecclesiology. The Articles thus ensure that Anglican theology and practice remain grounded in the central tenets of the Reformation, even as they allow for a breadth of expression within these boundaries. This theological foundation shapes the Anglican approach to right desire, always orienting our affections towards God's prevenient grace and the finished work of Christ.

Right Desire amid Anglican Division

Although we have a rich spiritual and theological foundation to build upon, Anglicans face significant challenges, both internal and external. Internally, we encompass a spectrum of churchmanship, from charismatic to evangelical and reformed to Anglo-Catholic, each with its own emphases and priorities. Some prioritize the reformed heritage of Anglicanism, emphasizing the authority of Scripture and the importance of salvation by grace through faith. Those more committed to the great catholic tradition put a greater accent on sacramental theology and liturgical practice. There are also – as everyone knows – strong disagreements about women’s orders and the nature of the priesthood. While diversity can provide a source of richness (the church is a body with many members) the vitriol sometimes surrounding these disagreements has the potential to cause breakdown and permanent division.

Internal Challenges

Our great challenge is to embrace diversity in churchmanship and simultaneously pursue unity, all while steadfastly seeking and submitting to God's truth, even on controversial topics where disagreements run deep. Remembering that “rightly ordered love” is the heartbeat of our tradition can, at least, inform our attempts to work through our most heated controversies. We do not need to set aside truth while we advocate for it both within and outside the church, always “in love” (Eph. 4:15).

One of the great strengths of Anglicanism has been its ability to hold together a variety of biblically faithful and orthodox theological emphases within a common tradition. However, this diversity can also lead to tension and division. A renewed focus on right desire offers a unifying principle that resonates across the spectrum of Anglican churchmanship. Christians through the ages have insisted that God’s love is prior to human love and is, in fact, the condition making human love possible. We love because he first loved us (1 John 4:19).

Right Desire among the Reformed

For those of a more reformed bent, an emphasis on right desire fits well with the emphasis on God's sovereignty and the need for human desires to be conformed to God's will. It echoes Calvin's insistence that true knowledge of God and self are inextricably linked. Calvin's vivid description of human nature as a "boiling restlessness" captures the state of disordered love that characterizes fallen humanity. This restlessness, Calvin argues, stems from our misplaced affections and can only be quieted through a reorientation of our loves towards God. The Westminster Shorter Catechism's first question – "What is the chief end of man?" – with its answer "To glorify God and enjoy Him forever," speaks directly to this right ordering as the solution to our restless condition.

Reformed theology's emphasis on the depravity of human nature acknowledges the universal tendency toward disordered love – a turning of the self away from God and towards created things. This disordered state manifests as the "boiling restlessness" Calvin describes, a constant churning of desires that can find no lasting satisfaction in created things. The doctrine of election, in this light, becomes God's gracious reordering of human loves, drawing the elect back to their proper orientation towards Him. This is what Calvin means when he writes of the "quickening" that accompanies new birth in Christ.2 Through this quickening, the restless heart begins to find its rest in God, as the Spirit works to realign our loves according to their proper order.

Right Desire Among the Catholics

For those of a more Catholic sensibility, right desire connects deeply with sacramental theology and the transformative nature of liturgy. In the Anglo-Catholic tradition, the sacraments are essential means of grace, reordering our loves by drawing us into deeper communion with God and one another. The Eucharist, in particular, is a powerful expression of rightly ordered love, where Christ’s self-giving love is made present, and we, in turn, offer ourselves as living sacrifices. This sacramental participation echoes Augustine’s teaching that true love is directed toward God, with all other loves properly oriented beneath it.

Additionally, Anglo-Catholics emphasize the formative power of liturgical worship, which shapes the desires of individuals and communities. The rhythm of daily prayer, the sacraments, and the Church’s liturgical seasons guide believers through the mysteries of Christ's life, death, and resurrection, reorienting their hearts toward God's love. This tradition holds that spiritual transformation happens through both word and ritual, as God works through the tangible elements of worship to align our affections and desires to His divine will. The communal nature of worship also reflects the belief that right desire is not solely an individual pursuit, but something cultivated within the body of Christ.

Right Desire Is a Key Point of Unity

A focus on rightly ordered love serves as a compelling bridge between the diverse theological traditions within Anglicanism. It provides a shared language that honors both Reformed and Catholic emphases, uniting them in their mutual recognition of the primacy of God's love. This framework not only reinforces our theological richness but also strengthens our communal identity, presenting a unified witness to the world. In short, different churchmanship can be entirely legitimate and need not lead to acrimonious division. In a tradition that is both catholic and reformed, the accent can be placed on one or the other so long as the accent does not lead to a neglect or rejection of the unaccented parts of the tradition.

I began this project considering the different ways that Anglicans receive the English Reformation. I noted that some Anglicans are prone to say:

“The English Reformation enables the proper reception of catholic faith - Yay catholic faith! All hail St. Augustine - let’s protect and keep the ordo amoris tradition handed down to us.”

And other Anglicans are prone to put the accent elsewhere:

“The English Reformation enables the proper reception of the catholic faith - Yay English Reformation! All hail Cranmer, Latimer, and Ridley! Let’s keep and protect the treasure of reformation doctrine, handed down to us.”

So long as neither the deep catholic heritage or the reformational emphasis on grace and faith are neglected or rejected, then we can say that Anglo-Catholic and Reformational Anglicans are both absolutely committed to the right ordering of love via the gospel of salvation by grace through faith in Jesus Christ. Both forms of churchmanship can recognize the centrality of right desire in the Anglican Way. This approach, rooted in the biblical imperative to love God above all and our neighbors as ourselves, offers a way to engage in difficult discussions while maintaining the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace.

There are obviously more differences among these two expressions of Anglicanism than I’ve mentioned here. There are stylistic and theological differences in liturgy, vestments, sacramental observance, church architecture and art, the use of incense, and much more. In his preface to the 1549 Book of Common Prayer, Thomas Cranmer indicated that a single prayerbook would help bring unity and uniformity to the churches of England:

"And where heretofore, there hath been great diversity in saying and singing in churches within this realm: some following Salisbury use, some Hereford use, some the use of Bangor, some of York, and some of Lincoln: now from henceforth, all the whole realm shall have but one use."

Likewise, the preface to the 1662 suggests that uniformity is important:

"Our general aim therefore in this undertaking was, not to gratify this or that party in any their unreasonable demands; but to do that, which to our best understandings we conceived might most tend to the preservation of Peace and Unity in the Church.”

Still, a diversity of styles need not contradict the call for “Peace and Unity in the Church” so long as a common prayerbook is maintained, the rubrics are followed, and the theological heartbeat is clearly heard in all forms of churchmanship. The 1662 wold seem to allow this kind of diversity:

It hath been the wisdom of the Church of England, ever since the first compiling of her publick Liturgy, to keep the mean between the two extremes, of too much stiffness in refusing, and of too much easiness in admitting any variation from it.

Rightly Ordered Love in Heated Controversies

Likewise, a proper focus on the gospel – i.e., we love because Christ first loved us - offers a fruitful paradigm for working through divisive issues, such as that of women’s orders. When approaching contentious issues like women's ordination, Anglicans would do well to remember Paul's admonition in 1 Corinthians 8 that "knowledge puffs up, but love builds up." This doesn't mean abandoning the pursuit of theological truth, but rather approaching it with humility and charity. It is clear that, for Paul, love has priority over knowledge -- not because knowledge doesn't matter -- but because Love gives shape to our knowledge (See 1 Cor 8 and 13).

Throughout church history, from the early church councils to the Reformation, Christians have had to wrestle with complex theological issues. The goal has always been to maintain both truth and unity, and an appreciation for ordering our loves rightly can guides us in this effort. The goal isn't to tolerate error, but to create an environment where truth can be pursued more effectively. When we approach disagreements with humility and love, we're more likely to listen, understand, and potentially be corrected if we're wrong.

I’ll necessarily leave this argument unfinished, but I would like to point out that, for Augustine, this deeply biblical principle was at the heart of nearly all his major theological projects, from the proper ordering of families to just war to the nature of salvation and the good life. In other words, the paradigm is deep enough that it can frame a comprehensive vision of the whole, which is necessary since the various aspects of Christian life fit together for the glory of God and for the ultimate good of all people. We are obviously not obliged to agree with Augustine’s writings. Although he was among the greatest of the church fathers, he is a mere Christian interpreting God’s Word in his own time. However, we would do well to learn what we can from him; certainly, we should not say to this important member of Christ’s body, “I don’t need you!” (1 Cor. 12:21).

At the moment – and largely due to the ubiquity of social media – we have too much polemics within Anglicanism and the result is that the world may fail to see the deep unity that holds us all together. Looking to the past, we see that the greatest of our Christian ancestors built the church up in love and unity. We can and should do the same.

A focus on the principle of right desire and all its implications can be the kind of foundation upon which to build – that is the biblical way and the way of Augustine and Cranmer.

Right Desire in a Post-Christian Society

Externally, we confront a post-Christian society that often views traditional Christian morality with suspicion or outright hostility. The rapid shift in cultural norms, particularly around issues of sexuality and gender, has placed orthodox Christian teaching at odds with mainstream culture. Moreover, the rise of secularism has led to a decline in religious literacy, making it more challenging to communicate the gospel effectively. We find ourselves in a position where we must not only proclaim the truth of Christ but also explain basic Christian ideas that were once widely understood.

The principle of rightly ordered love can provide a robust foundation for our witness in an increasingly secular culture. As we face the challenges of communicating the gospel in a post-Christian society, ordo amoris offers a framework for engaging with the deep longings and desires that characterize our human experience. This approach, which missiologists call "subversive fulfillment," allows us to present the Christian faith not as a repudiation of human desires, but as their true and ultimate satisfaction. This longing for fulfillment, so deeply embedded in human nature, finds its ultimate answer in the comprehensiveness of Christian truth. The desires that stir within us are not only acknowledged by the gospel but are brought to their rightful end in Christ.

In 2 Corinthians 10:5, the apostle Paul declares the superiority of Christian faith over pagan and secular ideologies, saying “we destroy arguments and every lofty opinion raised against the knowledge of God, and take every thought captive to obey Christ.” For Paul, the truth of Jesus Christ shines a light on all other truth claims, exposing their error but also recognizing whatever incomplete and unfulfilled truth they may possess (Eph. 5:11-13; Rom. 1:18-20). The Christian faith is not just one truth among others but the totality of Truth, something more like the pattern fastening all the jigsaw pieces together while simultaneously revealing the ultimate nature and purpose of each part. In Jesus Christ “all things were created” and in him “all things hold together” (Col. 1:15-17). This is what medieval theologians meant when they affirmed that theology is the “queen of the sciences.” It is the deepest of truths, which gives context and purpose to all others.

In the book of Acts the early church demonstrates great skill in showing how the gospel of Jesus Christ fulfills the hope of Israel in a subversive and unexpected way. See, for example, those sermons where Jesus fulfills the hopes of Israel:

Peter at Pentecost (Acts 2:14-40)

Peter at the Temple (Acts 3:12-26)

Peter before the Sanhedrin (Acts 4:8-12)

Stephen's speech before his martyrdom (Acts 7:2-53)

Peter at Cornelius' house (Acts 10:34-43)

Paul in Antioch of Pisidia (Acts 13:16-41)

In Acts 17:22-31, Paul presents Jesus as a subversive fulfillment of gentile desires when he addresses the “men of Athens” at the Areopagus. Consider his approach, which can be outlined as follows:

He finds a point of connection in the “loves” of the of men of Athens:

Paul observed an altar dedicated "To an Unknown God" (Acts 17:23)

He acknowledged the Athenians' religious nature (Acts 17:22)

He affirms what is true:

Rather than rejecting their polytheistic worship, Paul affirmed their unknown god and used it as a starting point for dialogue

He quoted their own poets to support his arguments (Acts 17:28)

Paul then reorients or “re-narrates” the worship of the Athenians:

Paul declared that the unknown God they worshipped was actually the one true God, creator of all things (Acts 17:24-25)

He challenged their understanding of deity , suggesting that God doesn't live in human-made temples or need anything from humans (Acts 17:24-25)

Finally, Paul suggests that Christ fulfills the hope of Athens, proclaiming that the unknown God can be known through Jesus Christ (Acts 17:30-31) who is raised from the dead and will judge the world in righteousness.

Paul engaged Athenian beliefs, convictions (the desires of their hearts) while simultaneously challenging and reframing them within a Christian context. This method was subversive in that it undermined the foundations of their polytheistic beliefs, but it also sought to fulfill their religious longings by commending the true God.

This approach has been embraced by some of the greatest theologians and church leaders throughout Christian history.3 When the church has thrived in hostile cultures, it has often done so by carefully examining the hopes, aspirations, and deepest convictions of people within that culture and then presenting the gospel as a transformative fulfillment of those very hopes, aspirations, and convictions. Interestingly, Tom Holland’s wonderful book, Dominion, shows that all the greatest ideals of our secular western culture are mere caricatures of the christian fullness from which they first emerged. Thus, Christianity is the forgotten fulfillment of the West’s current restlessness. A great deal of evangelistic and apologetic strategy can be mined from this great book. It’s especially important to note that Holland began writing this book as an atheist and finished it as a converted Christian.

Throughout history, christians have employed subversive fulfillment as an evangelistic and apologetic strategy. For instance, Augustine skillfully engaged with the Roman obsession with glory and eternal fame, a desire he recognized as fundamentally disordered. Rather than dismissing this aspiration outright, he redirected it, arguing that true glory is found not in fleeting earthly acclaim but in the eternal city of God. In Book V of City of God, Augustine writes:

"But the glory of that city in which they wish to reign is not that which human judgment applauds, but that which God, the infallible judge of truth, approves. If they seek true glory, even in this life, let them take away pride and put on charity. Thus they will possess felicity here, and in that city which is to come they will receive glory eternal." (City of God, 5.19)

Augustine here acknowledges the deep-seated Roman desire for glory, but he exposes its disorder - it seeks the praise of fallible humans rather than the approval of the infallible God. He then offers a subversive fulfillment: true glory, both in this life and the next, comes through humility and love. This redirection maintains the core desire for significance and lasting effect while reorienting its object and means of attainment.

Furthermore, in Book XIV, Augustine more explicitly ties this disordered desire for glory to the fundamental problem of misdirected love:

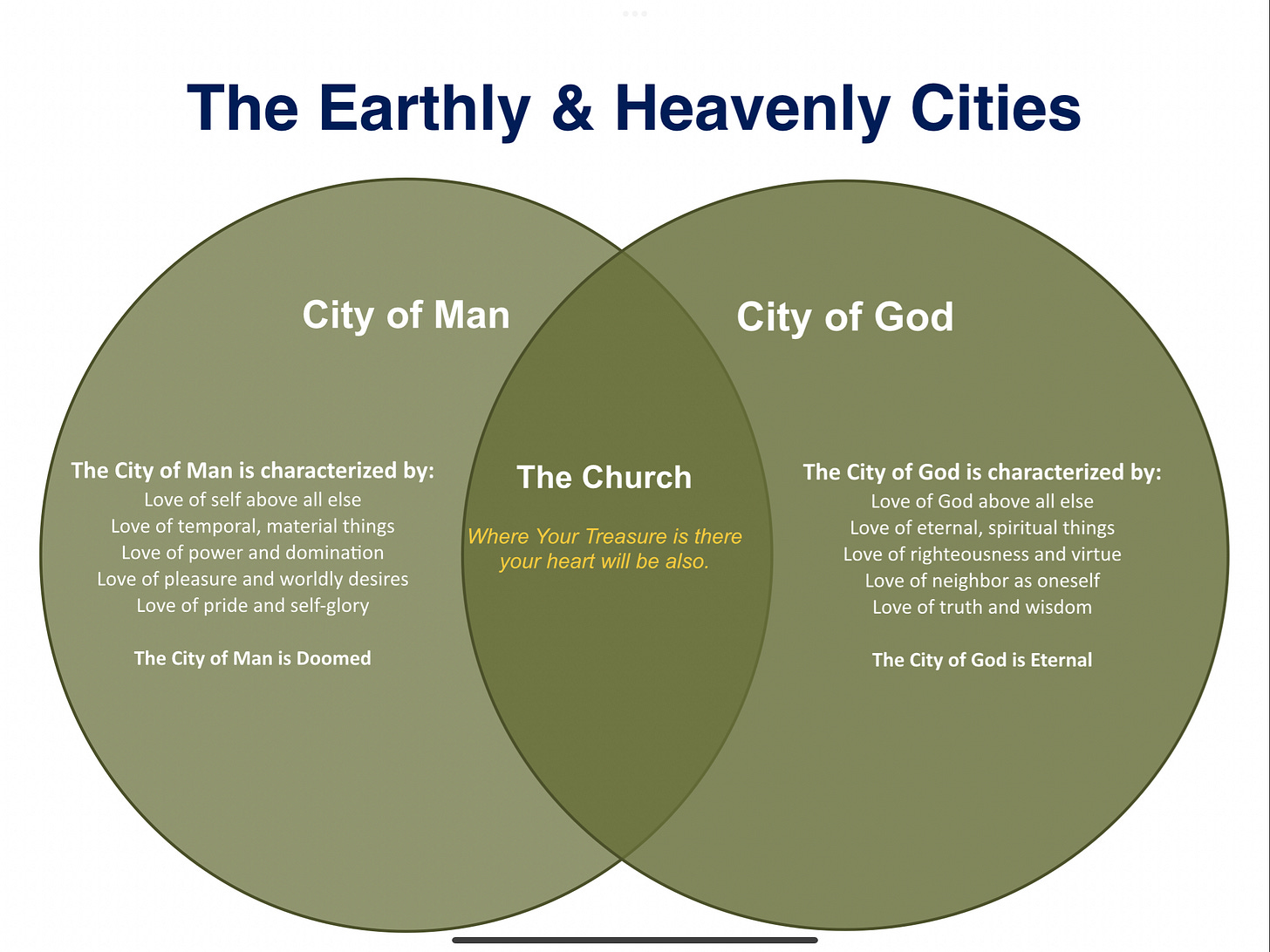

"Two cities have been formed by two loves: the earthly by the love of self, even to the contempt of God; the heavenly by the love of God, even to the contempt of self. The former, in a word, glories in itself, the latter in the Lord." (City of God, 14.28)

For Augustine the Roman pursuit of glory was symptomatic of a deeper disorder - love turned inward rather than toward God. By reframing glory in terms of rightly ordered love, Augustine offers a profound critique of Roman values while simultaneously presenting a path to their true fulfillment in Christ.[ii]

In The City of God, Augustine describes two societies differentiated by the loves that direct their citizens. These societies and citizenships appear mixed here on earth, but the ultimate love motivating all people will determine their final destination. The Church, in Augustine’s thoroughly biblical telling, is like a hospital rightly ordering the loves of those gathered to Jesus Christ by Word and Sacrament.

Subversive Fulfillment in Our Own Time

The “desires” of a people – even if those desires are disordered – always offer a point of connection where Christians can present the gospel as the means to find peace and rest for weary and restless souls.

All the resources of the Anglican tradition are tuned to the right ordering of disordered desire. Our tradition is therefore grounded in one of the bible’s deepest theological currents and perfectly suited for use in communicating the gospel in our weary, secular world.

Our tradition of rightly ordered desire offers a way to engage with some of the most influential ideologies in secular culture, providing a deep and fulfilling refuge for those seeking rest. Consider the following inflection points and their potential for fulfillment in Jesus Christ:

The Contemporary Quest for Identity: In a culture obsessed with self-discovery and self-expression, ordo amoris offers a profound insight: our true identity is found in rightly ordered love. Rather than rejecting the desire for authentic selfhood, we can show how loving God above all else paradoxically leads to the fullest expression of our unique personhood. As Augustine famously wrote, "You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it rests in you."

The Consumerist Pursuit of Pleasure: Our consumerist culture often promises fulfillment through the acquisition of experiences and possessions. The principle of rightly ordered love doesn't deny the goodness of pleasure but reorients it. We can argue that the deepest and most lasting pleasure comes from loving what is truly worthy of love, with God as the highest good. This allows us to affirm the desire for joy and satisfaction while pointing to its ultimate source and end.

The Worship of Unrestrained Freedom “You Do You”: Secular notions of freedom often focus on the absence of constraints. Ordo amoris offers a more profound vision of freedom as the ability to love rightly. We can engage with the cultural desire for autonomy by showing how submission to God's love actually liberates us from the tyranny of disordered desires.

The Epidemic of Loneliness and the Longing for Community: In an age of increasing isolation and fractured relationships, the Christian vision of rightly ordered love offers a compelling alternative. We can cultivate communities gathered on the basis of God’s love and forgiveness.

Concern for Justice: Many in our society, especially younger generations, are passionate about social justice. The principle of ordo amoris allows us to affirm this desire while grounding it in the righteousness of God. We can demonstrate how a properly ordered love for God leads to a love for justice that is both more profound and more sustainable than secular alternatives. Interestingly, in the Greek New Testament, the word dikaiosune is translated sometimes as “righteousness” and sometimes as “justice,” suggesting that we can never have one without the other.

The Proliferation of Knowledge: In an age flooded with information, emphasizing the right ordering of love reminds us that true knowledge involves an assimilation to what is known. Knowledge of God is inseparable from love of God and neighbor because love is the way we are assimilated to God. With the rise of artificial intelligence, our culture is overwhelmed by a surplus of knowledge, diminishing its value and complicating the goals of education. Focusing on rightly ordered love reorients the pursuit of knowledge, grounding it in the deeper pursuit of wisdom.

These examples are meant to suggest that the Anglican tradition, as an excellent pathway for being merely Christian, provides a robust position from which to communicate the gospel of Jesus Christ to a hurting world. The struggles of the world today, as in all ages, stem from disordered loves. The Anglican Way is grounded in God’s prior love poured out for us on the cross of Jesus Christ. The prayerbook tradition offers a continual reminder of God’s love and invites us into a fellowship continually ordered by that love.

Conclusion: The Significance of Right Desire

While sound doctrine is undoubtedly crucial to the Christian faith, the Anglican tradition, in alignment with the broader catholic tradition, recognizes that right desire is even more fundamental. This emphasis on ordo amoris provides a crucial context for doctrine, preventing us from becoming overly doctrinaire or legalistic in our approach to faith. Consider the Collect for Purity, which opens the Anglican Eucharistic liturgy:

"Almighty God, unto whom all hearts be open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid: Cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of thy Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love thee, and worthily magnify thy holy Name; through Christ our Lord. Amen."

This prayer beautifully encapsulates the Anglican approach. It acknowledges God's omniscience regarding our hearts and desires, and it petitions for the Holy Spirit's cleansing work. But notice the goal: that we may "perfectly love" God and "worthily magnify" His name. The focus is not on perfect understanding or flawless doctrinal articulation, but on love and worship. The end or goal of clarifying beliefs about God is always greater faith and adoration of God.

Moreover, this emphasis on rightly ordered love provides a safeguard against the potential cruelty of misapplied doctrine. As G.K. Chesterton wisely observed, "The cruelty of heresy is that it is true in its particulars and false in its generalities." When doctrine is divorced from love, it can become a weapon rather than a means of grace. After publishing the first essay in this series, I received an email from an alumnus of Trinity Anglican Seminary, Dr. Jonathan Parker who now teaches at Berry College. Jonathan reminded me that, during his time at Trinity, professors often stated that “orthodoxy is never cruel.” This conviction came from Bishop C. FitzSimons Alison who served on Trinity’s Board of Trustees and had a tremendous influence on the reformational theology that shapes our institution to this day. In his book, The Cruelty of Heresy, “Fitz” reminds us that:

The human heart is a ‘veritable factory of idols’…. The heart is certainly ‘far gone from original righteousness,’ and it is a filter through which the gospel must pass in its hearing and its telling. Each heresy in its own way encourages some flaw in our human nature. Without appreciating this human factor one could be led to believe that orthodox is a relatively simple matter; the results of proper research and scholarship. The human factor makes us acknowledge that research and scholarship itself must pass through the heart of the researcher and the scholar.4

The Anglican Way, at its best, seeks to hold together right belief and right desire. The classic formularies of the Anglican way are all designed to shape not just our minds but our hearts - reordering our loves in accordance with God's design. This allows us to engage with doctrine not as an end in itself, but as a means of deepening our love for God and neighbor.

This is the catholic way, preserved and expressed in the Anglican tradition. It offers a path forward grounded in orthodox Christianity and responsive to the deep longings of the human heart – including the hearts of all those who are lost and need to hear the good news of God’s love poured out for us in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

The Anglican formularies are the foundational documents that define Anglican doctrine and practice. The main Anglican formularies include: (1) The Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion, (2) The Book of Common Prayer, (3) The Ordinal (included in the prayerbook), (4) The Homilies, and (5) The Catechism, which was also included in the first prayerbook. Importantly, some scholars will include a number of other sources, which were highly influential in the 16th century, such as the “primers” of Kings Henry, Edward, and Elizabeth, early English bible translations, etc. See Tim Patrick, Anglican Foundations: A Handbook to the Source Documents of the English Reformation, (London: The Latimer Trust, 2018) for an excellent overview of these source documents.

See John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book 3, Chapter 3, Sections 1-4.

Justin Martyr, in his "First Apology," argued that the Greek philosophical concept of the Logos (reason or word) found its true embodiment in Christ. He claimed that philosophers like Socrates had partial access to divine truth, but that this truth was fully revealed in Christ, the incarnate Logos. This allowed Justin to affirm the Greek pursuit of wisdom while showing its ultimate fulfillment in Christian revelation. The following quotation is from his First Apology: "For whatever things were rightly said among all men are the property of us Christians. For next to God, we worship and love the Logos, who is from the unbegotten and ineffable God, since He also became man for our sakes, that, sharing our sufferings, He might also bring us healing. For all the writers were able to see realities darkly, because of the seed of the Logos implanted in them. But the seed and imitation given to them were according to their capacities; hence they often contradicted themselves" (First Apology, Chapter 46). Clement of Alexandria provides another example in his approach to Greek education and culture. In his work "The Stromata," Clement argued that Greek philosophy and learning could serve as a "preparatory teaching" for the Gospel. He saw value in the intellectual pursuits of his culture, writing, “Before the Lord's coming, philosophy was necessary to the Greeks for righteousness. And now it assists towards true religion, being a kind of preparatory training for those who attain to faith through demonstration. For your foot is a lamp to my feet and a light to my paths, says the prophecy. Therefore, philosophy was a preparation, paving the way for him who is perfected in Christ" (Stromata, Book VI, Chapter 8). In the medieval period, Thomas Aquinas continued this tradition by engaging with Aristotelian philosophy, incorporating the great philosopher’s metaphysics and ethics into his articulation of Christian theology. In doing so, he showed how Aristotle’s philosophical insights – incomplete on their own - could find their true home within a Christian intellectual framework. Aquinas explains the logic of his own “plundering of the Egyptians” in the following quotation: “Since grace does not destroy nature but perfects it, natural reason should minister to faith, as the natural inclination of the will ministers to charity. Hence, the teachings of the philosophers, in so far as they have known the truth, have not been despised, but rather, purified from error, have been brought into service for the knowledge of faith" (Summa Theologica, I, q. 1, a. 8, ad 2). These examples demonstrate that early Church leaders and later Christian thinkers didn’t merely dismiss cultural aspirations. Instead, they aimed to reveal how these aspirations ultimately point to and find their fulfillment in Christ. This method of "subversive fulfillment" serves as a model for engaging with the longings and desires of our own secular era.

C. FitzSimons Alison, The Cruelty of Heresy: An Affirmation of Christian Orthodoxy (New York: Morehouse Publishing, 1994), 23.