In the last two essays, we explored the theological principle of 'ordo amoris' and its role in facilitating true knowledge of God in Christ (1 John 4:7-21). I will now examine the centrality of God’s Word in the Anglican prayerbook tradition. The liturgies within this tradition guide our reading of Scripture sacramentally, in ways that consistently emphasize God's prevenient love, manifested through the gospel of Jesus Christ. This emphasis aims to reorient our own loves in response to God's prior initiative. This approach to Scripture is, as we shall see, not a “method” employed by the early church, but a natural development among early christians, grounded in the deep conviction that God’s Word is living and active – it transforms those who read faithfully by inviting participation in God's redemptive work.

It is no accident that Holy Eucharist begins with this ancient prayer:

Almighty God, to you all hearts are open, all desires known, and from you no secrets are hid: Cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of your Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love you, and worthily magnify your holy Name; through Christ our Lord. Amen.

In what follows, we will examine the sacramental nature of Scripture, its role in Anglican worship, and the way the Book of Common Prayer serves as a powerful means for guiding our encounter with God's Word and embrace of his gospel.

ON THE SACRAMENTALITY OF SCRIPTURE

Regarding the Word of God and our encounter with it, we can make the following distinctions:

The eternal Word refers to the pre-existent, divine Logos - the second person of the Trinity who was "in the beginning with God" (John 1:1). This aspect of the Word emphasizes the eternal nature of Christ, His divine essence, and His role in the Godhead before the incarnation. The eternal Word is coeternal and coequal with the Father and the Holy Spirit.

The incarnate Word describes the eternal Logos made flesh in the person of Jesus Christ (John 1:14). This aspect focuses on the historical reality of God becoming human, taking on our nature while retaining His divine nature. The incarnate Word lived among us, revealing God's character and will through His life, teachings, death, and resurrection.

The written Word refers to the Holy Scriptures, both Old and New Testaments, which serve as the divinely inspired record of God's revelation to humanity. This aspect of the Word emphasizes the role of Scripture as the authoritative text through which we encounter and understand both the eternal and incarnate Word. The written Word, illuminated by the Holy Spirit, mediates our knowledge of God and guides our faith and practice.

Importantly, all we know of the incarnate Word and experience of the eternal Word is mediated to us by the written Word. Although the written Word does not contain or exhaust the fullness of the incarnate or eternal Word, it introduces us and facilitates our communion with that Word. It is a necessary sign, you might say; it is “sacramental.”

As John Calvin insisted, the Bible is essentially “the Language of the Holy Spirit.” Bible reading familiarizes us with the character and will of the eternal God revealed in the incarnation and therefore prepares us to apprehend him when he speaks to us through his Holy Spirit. The Christian life must entail a substantive immersion in the Word of God (Logos) via study, prayer, and worship. The end or goal of this immersion is true knowledge of God, or what Cranmer called “wholesome doctrine.”

Cranmer’s famous collect from Advent II comes to mind:

Blessed Lord, who caused all holy Scriptures to be written for our learning: Grant us so to hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them, that by patience and the comfort of your Holy Word we may embrace and ever hold fast the blessed hope of everlasting life, which you have given us in our Savior Jesus Christ; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

We find a similar emphasis on the transformative nature of God’s word in Cranmer’s Book of Homilies. Consider this teaching from Homily I, Part I:

The words of holy Scripture be called words of everlasting life (John 6.68): for they be GODS instrument, ordained for the same purpose. They have power to turn through GODS promise, and they be effectual through GODS assistance, and (being received in a faithful heart) they have ever an heavenly spiritual working in them: they are lively, quick, and mighty in operation, and sharper than any two edged sword, and enter through, even unto the dividing asunder of the soul and the spirit, of the joints and the marrow…. the hearing and keeping of [Scripture] makes us blessed, sanctifies us and makes us holy.” (Hebrews 4.12).

Scripture, like the sacraments, mediates the presence and transforming power of Jesus Christ. Indeed, sacrament and scripture are bound together tightly from the very beginning.

Notably, Richard Hooker had a famous disagreement with the Puritans. The Puritans, being much more strident, wanted less time spent on the reading of scripture in the liturgy. They wanted, instead, more time for teaching and preaching biblical doctrine. Hooker disagreed and argued that Scripture – even apart from the preaching of the Word, draws us into the presence of Christ and transforms us.1 We should be grateful to Hooker, because he kept us tethered to Apostolic Christianity with his emphasis on scripture’s sacramentality.

Before we delve into the specific characteristics of sacramental reading, it's important to understand the historical context that shaped this approach. The early church's understanding of scripture was deeply intertwined with their sacramental practices, particularly the Eucharist. This connection provides crucial insight into how they viewed and interpreted sacred texts.

Interestingly, the term 'New Testament' originally referred not to a collection of writings, but to the Lord's Supper itself. This linguistic connection reveals the profound link between the sacramental life of the early church and what would later become the canonical New Testament.2

Consider this from FX Durwell. He notes that

Holy Scripture is forever linked with that supreme sacrament of Christ’s body and the redemption, the Eucharist; the same name is used for both: ‘This Chalice,’ Our Lord said, ‘is the New Testament’; this book also we call the New Testament; chalice and book, each in its own way, contain the New Covenant, the mystery of our redemption in Christ.

Durwell calls our attention to the close developmental relationship between the sacramental life of God’s people and the canonization of sacred scripture. This relationship is true of the development of both the Old Testament and the New. In Ancient Israel, God’s presence was first associated with Temple and sacrifice. Only later did the people gather to hear God’s Word read in the synagogue. The Old Testament canon was gathered together and became an authoritative list of writings for Israel, only after its individual books were used for centuries in the gathered assembly. The same was true for the New Testament. It wasn’t until the late 4th century that Athanasius’s list of 27 recommended writings were determined canonical at several regional councils in North Africa (Council of Hippo in 393 & Council of Carthage in 397) under the authority of Augustine of Hippo. For several hundred years prior to those councils and the canonization of the 27 New Testament texts, those apostolic writings had been conceived in ways analogous to the Eucharist.

Consider the testimonies of the Early and Reformation Christians, regarding the relationship between word and sacrament.

Ignatius of Antioch, on his way to persecution, writes that he finds comfort by “taking refuge in the “Gospel” as in Jesus’ flesh.”

Origen wrote… “You who are accustomed to attending the divine mysteries know how, when you receive the body of the Lord, you guard it with all care and reverence lest any small part should fall from it, lest any piece of the consecrated gift be lost. For you believe yourself guilty, and rightly so, if anything falls from there through your negligence. But if you are so careful to preserve his body, and rightly so, why do you think that there is less guilt to have neglected God’s word than to have neglected his body?”

Athanasius declares that “the Lord Himself is in the words of Scripture.”

“Whatsoever the divine Scripture says is the voice of the Holy Spirit,” says Gregory of Nyssa.

Likewise, Jerome writes: “We have in this world only this one good thing: to feed upon his flesh and drink his blood, not only in the sacrament, but in the reading of Scripture.”

“The Bible is the Language of the Holy Spirit,” suggests John Calvin, much later. Calvin, incidentally, affirms the sacramentality of the Bible in the Institutes (4.14.4).

For these early Christians, it’s clear that the Nature and authority of scripture is analogous to the nature and authority of the Lord’s Supper. That is, the gospel witness of the New Testament canon is a means of grace used by God to draw us into his presence and conform us to Himself.

This historical context helps us understand why the early church approached scripture in a sacramental manner. They saw a continuity between Christ's presence in the supper and in the sacred texts. Notably, Thomas Cranmer is entirely in line with this older tradition when he writes:

“as drink is pleasant to them that be dry, and meat to them that be hungry; so is the reading, hearing, searching and studying of holy scripture, to them that desirous to know God, themselves, and to do his will,” (Homily One, in the Book of Homilies).

As I’ve hopefully demonstrated, Christians in ages past understood the Bible sacramentally - as analogous to the Eucharist in its mediation of Jesus Christ to God’s people. It should not surprise us, then, to find that the church has traditionally read and interpreted the scriptures sacramentally.

SACRAMENTAL READING

Sacramental reading has at least these two key characteristics. First, It is grounded in the church’s common, liturgical worship. Second, it has the formation of right desire, that is – assimilation to God in Christ - as its end.

Scripture in the Liturgy

In terms of the liturgy, consider that prior to the mass-production of Bibles, which began in the 15th century, all Christians (and Jews before them) encountered sacred scripture as, first and foremost, a liturgical script. They understood themselves as participants in a great drama authored and directed by the Triune God - the God in whom we “live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28). Liturgical reading of scripture allowed Christians to enter the story of God in mimetic fashion – identifying themselves with God’s people in biblical history. Think of medieval passion plays – we do something like this with the gospel reading on Palm Sunday in our own time.

Anglicans and other Christians typically attend to the whole story of salvation during eucharistic services on Sundays and Holy Days. Although this presentation is overly simplistic, we can say that a eucharistic liturgy generally has four basic movements:

The Gathering: Begins with a hymn, procession, prayers, and recitation of commandments. This mimics the gathering of Israel's tribes and Christ's disciples for redemption and witness.

The Word of God: Scripture readings from Old Testament, Psalms, Epistles, and Gospels, thematically linked to show God's covenant faithfulness through the entire canon.

Holy Communion: Reenacts Christ's passion through the Eucharist. Following Luther's understanding, this is the congregation's faithful response to God's Word, embodying self-sacrifice and union with Christ's body.

The Sending: Echoes Christ's post-resurrection commission to his disciples. The service concludes by sending worshippers out to continue Christ's mission.

This structure reenacts the gospel and invites worshippers to comprehend themselves as participants in God's providential work. Along with the Christian calendar (Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Easter, Pentecost, and Kingdomtide), liturgical engagement of the Bible means that we not only read but are invited to inhabit the Word so that we might be formed in faith, hope, and love, living within Gods work of creation, redemption, and the anticipated consummation of Christ's kingdom.

Importantly, with his production of the Book of Common Prayer, Cranmer ensured that Anglicans - like ancient Israel and pre-reformation Christians - would encounter the Bible, first and foremost, as a liturgical script and a book of transformation. Cranmer not only structured his liturgies according to the logic of the gospel, he also ensured that these liturgies are little more than the Bible itself arranged for prayer and worship. The Anglican liturgies from the Book of Common Prayer are infused with the Word of God, as is evident in the image below, taken from the 19th century text, The Liturgy Compared with the Bible. The words on the left come directly from the Collect for Purity in the 1662 BCP. The words on the right provide biblical references upon which the collect for purity is based. This text covers the entire 1662 Book of Common Prayer, proving that every sentence either directly quotes or is grounded in biblical truth.

Scripture Interpretation via the Quadriga

While liturgical engagement provides a gospel centered and biblically saturated framework for encountering Scripture communally, the ancient interpretive framework called the quadriga offered an approach to biblical interpretation that aimed at Christian formation. This way of reading Scripture was not really a method, but a structure for reordering the reader's desires and facilitating their assimilation to God.

The term "quadriga" is Latin and originally referred to a "four-horse chariot." However, in the context of biblical interpretation, it refers to a fourfold framework or sensibility for interpreting Scripture. This fourfold sensibility originated in Paul’s distinction between the letter and the spirit.

Such is the confidence that we have through Christ toward God. Not that we are sufficient in ourselves to claim anything as coming from us, but our sufficiency is from God, who has made us sufficient to be ministers of a new covenant, not of the letter but of the Spirit. For the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life. (2 Corinthians 3:4–6)

In the early church, theologians began to think of the spiritual sense of scripture as having three dimensions: the allegorical, tropological, and analogical. Thus, the quadriga really affirmed two basic senses of scripture - letter and spirit, but they further divided the spiritual sense into three. Therefore, the fourfold sense of scripture developed to include the (1) Literal (or Historical), (2) Allegorical, (3) Tropological (or Moral) and (4) Anagogical. Before I explain the enduring value of the quadriga, let me offer a brief qualification, which I will return to at the end of this section. The quadriga became increasingly problematic in the Middle Ages, as interpreters often lost contact with the literal/historical sense of the text. This led to allegorization that seemed to derive from the mind of the interpreter, rather than the mind of God. And it often was little more than a device to justify the inclinations of medieval clergy, as it did when Innocent III argued that his authority was greater than the king because, in Genesis 1, the Sun gives light to the moon. According to this most powerful of medieval popes, the he is represented by the sun, and the moon represents earthly kings. The Reformers were right to consider this interpretation eisegesis - reading something into the text that is certainly not meant to be there.

The Reformers rejected the quadriga and, following the humanists like Erasmus, began to pay much greater attention to the letter - the literal and historical sense of the text. This, of course, led to its own abuses with the development of historical critical scholarship, but that is another story. You can find my own work on the limitations and enduring value of the quadriga by clicking here.

Despite its misuse, the quadriga represented a spiritual inclination that really must and does endure into our own time. Among other things, the quadriga recognized the centrality of typology in biblical theology. No question, Jesus represented a new and perfect Adam, Moses and David. He was the true prophet, priest, and king and so much more. Events such as the exodus became enduring “types” to help us understand the nature of salvation. The promised land is a type of our eternal heaven. Our sacramental theology has a typological foundation that is rich and profound so that to enter the waters of baptism is to be plunged into the holy history of Israel, fulfilling the story of Noah and the ark, the crossing of the Red Sea, and the crossing of the Jordan. Likewise, in the Lord’s Supper, all of the sacrifices through the entire old testament are fulfilled in Jesus’ perfect sacrifice. When we partake, we are entering, not only into the body of Christ, but into an ancient people and their holy history, governed by God and united to Christ. The Bible communicates typologically and invites readers into a mimetic relationship with the history that it tells.

Additionally - and this is the matter at hand, the quadriga ensured that biblical interpretation was ordered to the right end - true knowledge of God as assimilation and rightly ordered love. This is what I’ll demonstrate below.

Just as the quadriga went astray when interpretation became too distanced from the literal/historical sense of the text, so does interpretation - such as the historical critical method - go astray when it is not focused on the proper end of interpretation. The Bible is a book of divine disclosure - to interpret it in any other way is to miss the mark.

The quadriga demonstrates how the early church understood Scripture sacramentally, given by God to shape human hearts of gratitude and hope, in response to his own prior love. By engaging with the text on multiple levels, readers were invited to encounter God's Word in a way that integrated intellectual understanding with spiritual formation, fostering the right ordering of love and drawing believers into deeper communion with God. Hugh of St. Victor explains the four-fold sense in his Didascalion:

The foundation and basis of holy teaching is history, from which the truth of allegory is extracted like honey from the comb. If then, you are building, lay the foundation of history first; then by the typical sense put up a mental structure as a citadel of faith and finally, like a coat of the loveliest of colours, paint the building with the elegance of morality. In the history you have the deeds of God to wonder at, in allegory his mysteries to believe, in morality his perfection to imitate.3

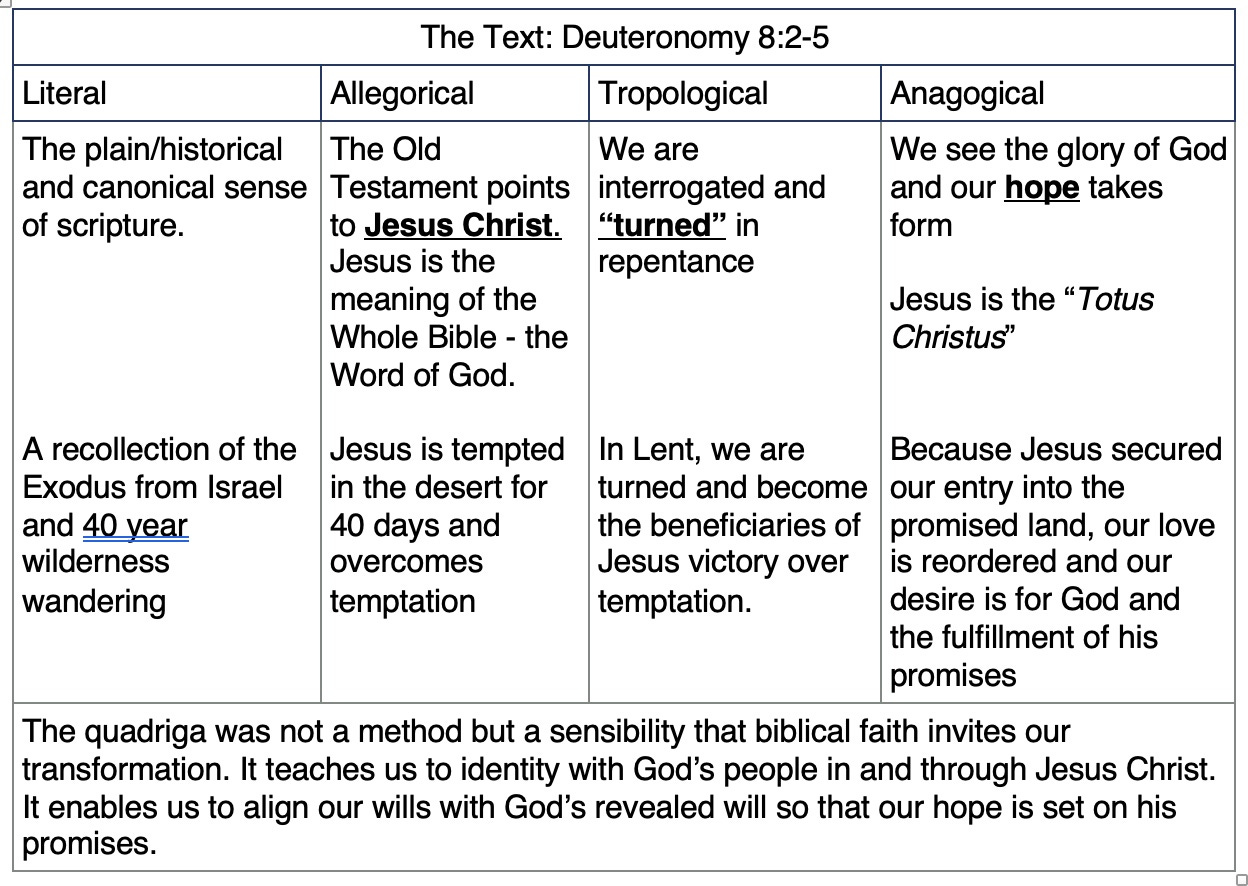

The chart below may help you visualize what a reader’s movement through the four senses might have looked like.

While the quadriga offers insights into scripture's transformative nature, medieval exegesis had limitations. As I mentioned above, a lack of historical insight often led to interpretations disconnected from the text's original context. However, contemporary scholarship need not abandon the rich tradition of spiritual reading, since we can retrieve its best insights while benefiting from modern biblical scholarship.4

I suggest two key principles for a renewed spiritual exegesis that avoids some of the excesses and errors of medieval exegesis. First, we can maintain deep respect for the literal sense of scripture. The historical-grammatical meaning of the text, understood in its original context, provides the essential foundation for all spiritual interpretation. Modern critical methods, when employed faithfully, can strengthen our spiritual reading by grounding it more firmly in the text itself.

Second, we must keep in view the ultimate purpose of biblical interpretation: to know God and be conformed to His will through a right ordering of love. The goal is not merely academic understanding, but transformation and wisdom - the reordering of our loves and desires in accordance with divine truth. This aligns perfectly with our Anglican emphasis on scripture as a means of grace, through which we encounter the risen Christ.

In practice, this means our engagement with scripture should be both intellectually rigorous and spiritually formative. We can employ the best tools of modern scholarship to understand the historical and literary dimensions of the text. Simultaneously, we approach scripture with hearts open to its power to shape our lives, always seeking to discern how God's eternal Word speaks to our present circumstances and ultimate destiny.

This balanced approach recognizes that the Bible's meaning is not exhausted by its original historical context, while also guarding against untethered allegorizing. Most importantly, it preserves the transformative power of God's Word which is continually forming Christ in us (Galatians 4:19).

The Anglican tradition, with its rich liturgical life centered on Word and Sacrament, already embodies and preserves the best of medieval exegesis without continuing its misuses. My purpose here is to show how this is the case.

Our Book of Common Prayer, saturated with scriptural language and imagery, invites us into a participatory engagement with the biblical narrative. Through this immersion, we find ourselves not merely reading an ancient text, but being read by it - challenged, comforted, and ultimately transformed by the living Word of God.

SACRAMENTAL READING IN THE BOOK OF COMMON PRAYER

The Book of Common Prayer beautifully exemplifies the best insights of medieval exegesis as it invites the congregation to read and engage scripture sacramentally. Consider the following prayers, taken from the liturgies for Baptism and Holy Communion. It would be easy to find illustrations like those I include here in all of the prayerbook liturgies, but for sake of time and space, I’ll only offer two examples.

These prayers demonstrate how Scripture is still engaged through the fourfold sense in our sacramental rites, inviting worshippers into a transformative encounter with God's Word. Consider this prayer from the thanksgiving over the water in the baptismal liturgy:

We thank you, Almighty God, for the gift of water. Over it the Holy Spirit moved in the beginning of creation. Through it you led the children of Israel out of their bondage in Egypt into the land of promise. In it your Son Jesus received the baptism of John in the River Jordan when the Holy Spirit descended upon him as a dove.

We thank you, Father, for the water of Baptism. In it we are buried with Christ in his death. By it we share in his resurrection. Through it we are reborn by the Holy Spirit. Therefore in joyful obedience to your Son, we bring into his fellowship those who come to him in faith, baptizing them in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit."

This prayer engages Scripture on all four levels:

Literal: References creation, the Exodus, and Jesus' baptism in the Jordan.

Allegorical: These water events converge and find their fulfillment in Christian baptism.

Tropological: We participate in Christ's death and resurrection through baptism, being "reborn by the Holy Spirit."

Anagogical: Points to our future resurrection and eternal life in Christ.

The Eucharistic prayer similarly demonstrates this multifaceted engagement with Scripture:

For on the night that he was betrayed, our Lord Jesus Christ took bread; and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and gave it to his disciples, saying, 'Take, eat; this is my Body, which is given for you: Do this in remembrance of me.'

Likewise, after supper, Jesus took the cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave it to them, saying, 'Drink this, all of you; for this is my Blood of the New Covenant, which is shed for you, and for many, for the forgiveness of sins: Whenever you drink it, do this in remembrance of me.

The prayer continues:

And here we offer and present to you, O Lord, ourselves, our souls and bodies, to be a reasonable, holy, and living sacrifice. We humbly pray that all who partake of this Holy Communion may worthily receive the most precious Body and Blood of your Son Jesus Christ, be filled with your grace and heavenly benediction, and be made one body with him, that he may dwell in us, and we in him.

This prayer also engages Scripture on multiple levels:

Literal: Recounts Jesus' actions at the Last Supper, grounding the Eucharist in historical events.

Allegorical: Christ fulfills the Passover and sacrificial system, establishing the New Covenant.

Tropological: We participate in Christ's death and resurrection, offering ourselves as "living sacrifices" (Romans 12:1).

Anagogical: Anticipates our union with Christ and the heavenly wedding feast of the Lamb (Revelation 19:9).

The liturgy concludes with a powerful, anagogical reminder of this eschatological hope: "Behold the Lamb of God, behold him who takes away the sins of the world. Blessed are those who are invited to the marriage supper of the Lamb."

To be clear, I am not arguing that Thomas Cranmer or other Anglican architects of our prayerbooks, have purposely followed the ancient fourfold approach. Rather, I am suggesting that the fourfold approach was right in its deepest intentions. The early Christians understood the importance of transformative reading. Our prayerbook is designed with the same deep, transformative intentions for our reading of scripture. The good that was accomplished by the quadriga is now accomplished with our prayerbooks.

This sacramental approach to Scripture in our liturgies is designed for assimilation to God. It engages the whole person - mind, heart, and soul. By encountering the Word through multiple senses simultaneously, we are invited into a deeper, more complete apprehension of God's revelation.

Moreover, the liturgies are designed to cultivate "right desire" in readers and hearers, helping to align our loves with God's purposes. As we participate in these liturgies, we are immersed in the holy history of God and his people, and that history becomes our own. Finally, we don't merely read and engage scripture in these liturgies, we are read by them. We are challenged, comforted, and by grace through faith, transformed by the living Word of God. The Book of Common Prayer thus serves as a powerful tool for mediating this transformative engagement with Scripture, preserving and making accessible the rich tradition of spiritual reading for contemporary Anglican worship. This formation entails at least the following features:

Multi-layered Interpretation: prayerbook liturgies ensure that our encounter with the truth of God’s Word engages our intellect as well as our imagination, moral sensibilities, and deepest hopes.

Christocentric Focus: sacramental reading is focused on the gospel of Jesus Christ, teaching us to place our hope in his promises.

Communal Experience: the prayerbook is for the people of God, gathered together under the authority of the Word. The church’s liturgical engagement of the Word helps to shape individual reading practices to accord with sound interpretation and evangelical theology.

Transformative Encounter: sacramental reading invites us to encounter the living God through the written Word, ordering our loves to conform with His will.

We should not forget that the Book of Common Prayer was, among the Anglican Formularies, the first project begun by Thomas Cranmer. The prayerbook was among his greatest gifts, not only to Anglicans through the ages, but to all Christians and to the world we are called to bless.

The prayerbook is a mediating document; it captures what is best of the deeply transformative spiritual sensibility of the early and medieval church and develops this sensibility - helpfully and necessarily - with the infusion of reformation doctrine, including a right emphasis on salvation by grace through faith. As Ashley Null has insisted, the Book of Common Prayer is saturated with reminders of God’s exceeding love for us and is intended to encourage and facilitate our loving response to God, our maker and redeemer.

In a recent conversation with Archbishop Bob Duncan, I learned this great quip from Null: “Cranmer so wanted BCP worshippers to know the awesome love of God that they would love God more than their own sin.”

The liturgies of the Book of Common Prayer involve us in a thoroughly sacramental encounter with sacred scripture that keeps what is most valuable in medieval exegesis without continuing its excesses and abuses . They help us to “read, mark, and inwardly digest” God’s Word. They form our minds in the truth, goodness, and beauty of God’s Word and mediate the biblical call to repentance and to the right ordering of our desires.

CONCLUSION

In short, the Book of Common Prayer stands as a cornerstone of the Anglican Way – perhaps Cranmer's greatest gift with the most immediate bearing upon the lives of Christians. The prayerbook, in accordance with Article VI of the Thirty-Nine Articles, immerses us in God’s Word with every gathering. It keeps the church grounded in the “faith once and for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 1:3) and holds Word and Sacrament together at the center of Christian life. The Book of Common Prayer, with its biblical saturation and liturgical framework, is designed to help us "read to love." Accordingly, Anglicanism represents a biblically faithful, gospel centered development of the apostolic faith and continues to offer an excellent way to be a Christian.

ENDNOTES

Richard Hooker, The Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity 5.22.13.

Matthew 26:28 (KJV): "For this is my blood of the new testament, which is shed for many for the remission of sins."Mark 14:24 (KJV): "And he said unto them, This is my blood of the new testament, which is shed for many."Luke 22:20 (KJV): "Likewise also the cup after supper, saying, This cup is the new testament in my blood, which is shed for you."1 Corinthians 11:25 (KJV): "After the same manner also he took the cup, when he had supped, saying, This cup is the new testament in my blood: this do ye, as oft as ye drink it, in remembrance of me.

Hugh of St. Victor, Didascalicon, VI.3

For a comprehensive exploration of de Lubac's approach to spiritual exegesis and its implications for contemporary theology, see Bryan C. Hollon, Everything is Sacred: Spiritual Exegesis in the Political Theology of Henri de Lubac (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2009). The conclusion focuses specifically on principles for contemporary adaptation of medieval exegesis.

Thanks for this essay, Bryan. Enlightening.

The four categories are helpful, and I share your concern/observation about allegory. It often says more about the interpreter and reader. The use of allegory is rampant today, even in the pulpit and with many of our church leaders. I have heard too many sermons about how we (as the church) are following a pillar of fire by night into the promised land, etc. It gets old because it is sloppy.

I suggest a new word for allegorical. Typological.

However, Gordon Fee said, "The text (bible) cannot mean what it never meant." That has been my mindset when I have prepared for teaching or preaching. But the four categories really don't agree with Fee's statement.

I'm left to ponder...