I wrote this essay in 2013 for a conference presentation, which is why the argument is somewhat experimental and provocative. It was intended to stimulate conversation, and I believe it still has potential to do so. At some point, I’d like to flesh-out the argument and turn it into a book titled, The Sacramental Word.

My thesis is simple though two-fold. First, the doctrine of scripture remains surprisingly under-developed in Christian thinking, and while this is especially true in protestant theology, there is work to be done among Roman Catholic and Orthodox scholars as well.[1] Second the classical idea that scripture is sacramental in nature – so much so that it has been referred to as the “Sacramental Word” by reformed, catholic, and orthodox theologians – holds great promise if we want to develop the doctrine of scripture more fully in relation to the triune God and his economy of grace.

Evidence of Underdevelopment

Protestant systematic theologians often treat scripture as prolegomena in order to establish its authority before moving on to the truly “synthetic” material. Within this paradigm, the doctrine of scripture is treated as a part of the doctrine of revelation. In the many theology texts that follow this pattern, we find in a treatment of the bible, discussions of inspiration, inerrancy, perspicuity, necessity, and sufficiency. Thus, the bible is conceived as a relatively static body of knowledge that has been inspired by God. It contains no errors in its description of God and God’s work. Its meaning is clear, and this given, perfect, clear body of knowledge is entirely necessary for those hoping to know God in order to receive his saving grace. This view is sometimes described as foundationalism, and although I’ve offered a bit of a caricature, the description is not entirely unwarranted.

Within this reigning evangelical paradigm, Holy Scripture is affirmed as God’s Word, and its divine authority is defended, often with reference to the reliability of ancient manuscripts. But how exactly does the bible relate to the Triune God, materially? The Bible is a created thing, in other words, but what kind of created thing is it? Why is it accorded such authority, and what does it have to do with God and our salvation?

Is the bible principally source material like a textbook or encyclopedia? Or is there some more organic connection between Holy Scripture, the life of God and the life of the church that needs to be fleshed out? Obviously, I believe that there is as would most Christians, I suspect. But in order to flesh things out properly, I am suggesting that that the doctrine of scripture needs to be more fully developed.

Occasionally theologians will suggest that the bible has a sacramental quality. The church fathers clearly understood the Bible in this way, as did the reformers and especially John Calvin.[2] Among contemporary reformed theologians, Michael Horton has taken an interest in the sacramental Word in several recent works.[3] Likewise, Roman Catholic and Orthodox theologians speak of the sacramental nature of the Word. Though his remarks are brief, F. X. Durwell’s classic little book, Eucharist: Presence of Christ[4] offers a good example as does Alexander Schmemann’s book, The Eucharist: Sacrament of the Kingdom. But in most of these examples, and in all of the examples that I am aware of, scholars have emphasized the sacramental nature of scripture for the purpose of underscoring what the Word does (especially when it is preached in the gathered assembly) rather than what it is in relation to the economy of grace.

Yet, among Roman Catholic scholars, there are occasional suggestions that, in Sacred Scripture, we encounter the “real presence” of Christ in a way that is analogous to the real presence in the Eucharist – that is – a presence, which is materially mediated. Scott Hahn, for instance, suggests that,

Scripture conveys the divine Word….in a way that is analogous to sacramental efficacy. That is why the Church has traditionally understood the Scriptures to be without error. Yet “without error” does not adequately describe the extent of the Bible’s sacramentality. Other books can be free of error— for example, a well-edited algebra textbook in its eighth edition—but no other book has God as its author, and so no other text conveys God’s saving power so purely…. Scripture’s authority is thus an extension of Christ’s own authority, and its characteristics are analogous to those of Christ Himself.[5]

And this gets to the heart of my interest in this subject. Christians believe that the bible is the Word of God, that Jesus Christ, the divine logos, is truly present to us in and through the Sacred Page. Yet, Christians do not believe that the bible is a member of the Godhead – a fourth member of the Trinity, so to speak. The Bible is not God, but Jesus Christ, the Word of God, is present to us in and through its inspired texts. But how so?

What I would like to suggest is that the language of sacrament is not only consistent with the great tradition but that it remains the best language available to us if we want to make a case for the real presence of Christ in Sacred Scripture. And by the way, almost all evangelicals affirm something akin to a “real presence” theory with regard to the bible even if they recoil from such an idea with regard to the sacraments. This should give us pause, I think.

But back to the argument, the Bible is not God, yet it is Divine – how so? Well, Scripture is sacramental, not only because its efficacious in a utilitarian sense but also because we encounter the real presence of Christ in and through it. I’m not suggesting that the Bible or even the proclamation of the gospel in the gathered assembly should be classified a sacrament in the strict sense, along with baptism, Eucharist, etc. I will, however, follow others in emphasizing the co-dependency and co-inherence of the Word and the formal sacraments.

Now I want to turn to the matter of doctrinal development and consider why the doctrine of scripture remains under-developed.

Doctrinal Development

It is common knowledge that Christian doctrines have developed, through the ages, for a variety of reasons. Often doctrinal development follows the principle of lex orandi, lex credendi (the rule of prayer is the rule of belief) and in response to some overreach on the part of a soon-to-be heretic. Arius of Alexandria, for example, could not abide the idea that Christ is both God and Man, so he sought to eliminate one side of the paradox, arguing that Jesus Christ is not God.

Yet, Christians had, since apostolic times, worshiped and prayed to Jesus Christ as God. Nicene Christology developed, therefore, as the church struggled to find language, which could adequately clarify the beliefs inherent in its own worship practices – making more explicit those truths, which had been believed implicitly for many years.

What interests me, though it is slightly less well known, is that highly technical theological formulations in sacramental theology arose for reasons similar to the development of technical Christological language. Namely, Eucharistic realism was evident in the Church’s sacramental practices from the beginning, and the technical doctrine of transubstantiation arose only when Eucharistic realism was called into question.[6]

Although I could offer a litany of quotations endorsing Eucharistic realism including a long list of apostolic fathers, apologists, doctors of the Church and even ecumenical councils (see Council of Ephesus, Session 1, Letter of Cyril to Nestorius [A.D. 431]), I’ll offer just a few characteristic quotations, which every Roman Catholic is likely to have heard before.

From 1 Cor. 10:14-18: Therefore, my beloved, flee from idolatry. 15 I speak as to sensible people; judge for yourselves what I say. 16 The cup of blessing that we bless, is it not a participation in the blood of Christ? The bread that we break, is it not a participation in the body of Christ?17 Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread. 18 Consider the people of Israel:[a] are not those who eat the sacrifices participants in the altar?

From Justin Martyr: We do not consume the eucharistic bread and wine as if it were ordinary food and drink, for we have been taught that as Jesus Christ our Savior became a man of flesh and blood by the power of the Word of God, so also the food that our flesh and blood assimilates for its nourishment becomes the flesh and blood of the incarnate Jesus by the power of his own words contained in the prayer of thanksgiving.

From Cyril of Jerusalem “The bread and the wine of the Eucharist before the holy invocation of the adorable Trinity were simple bread and wine, but the invocation having been made, the bread becomes the body of Christ and the wine the blood of Christ” (Catechetical Lectures 19:7 [A.D. 350]).

From Augustine: “What you see is the bread and the chalice; that is what your own eyes report to you. But what your faith obliges you to accept is that the bread is the body of Christ and the chalice is the blood of Christ.

As these quotations illustrate, and J.D.N. Kelly insists, for the Church Fathers “Eucharistic teaching… was in general unquestioningly realist, i.e., the consecrated bread and wine were taken to be, and were treated and designated as, the Savior’s body and blood.”[7]

However, after some began to downplay Eucharistic realism in the 11th century (Berengar of Tours), the highly technical Aristotelian language of substance and accident was utilized in the development of the doctrine of transubstantiation as an effort to guard and more precisely articulate what the church had always accepted implicitly -– that Christ is really present in the Eucharist. This is precisely the principle of lex orandi, lex credendi at work.

Now, although the doctrine of transubstantiation is often caricatured in Protestant thinking, these objections typically stem from a misunderstanding of the Aristotelian categories of substance and accident, which I will explain in a moment.[8]

I’d like to suggest, however, that there is much to gain by a careful consideration of the rationale behind transubstantiation. Although I have no interest in defending the doctrine of transubstantiation and certainly not Roman Catholic veneration of the host, which I find objectionable, I do believe that the logic of transubstantiation can be helpful and highly instructive regarding the nature of sacramental grace.

Namely, the doctrine of transubstantiation, as articulated by Thomas Aquinas, was a brilliant and I believe laudable attempt to firmly situate Eucharistic realism within a liturgical context and ultimately within the context of God’s economy of grace, which is re-presented –materially – in the Mass. In other words, the doctrine of transubstantiation was meant to ensure that the Eucharist is conceived as a channel or means of grace that calls to mind and invites our participation in the whole biblical drama of salvation. This drama of salvation is, of course, reenacted in every Eucharistic liturgy.

It is interesting to note that the great Orthodox theologian, Alexander Schmemann was often critical of Western Eucharistic theology, suggesting that the question of how and whether the elements of bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ has been a distraction from the much more important matter of the relationship between the Eucharist and the liturgy as a whole – or between the Eucharist and the drama of salvation, to put it in simpler terms. For Schmemann, [and I quote] “the liturgy of the Eucharist is best understood as a journey or procession. It is the journey of the Church into the dimension of the Kingdom,”[9] He argues further:

It is indeed one of the main defects of sacramental theology that instead of following the order of the Eucharistic journey with its progressive revelation of meaning, theologians applied to the Eucharist a set of abstract questions in order to squeeze it into their own intellectual framework. In this approach what virtually disappeared from the sphere of theological interest and investigation was liturgy itself, and what remained were isolated ‘moments,’ ‘formulas’ and ‘conditions of validity.’ What disappeared was the Eucharist as one organic, all-embracing and all-transforming act of the whole Church.[10]

Schmemann, like Henri de Lubac, held that the Eucharist actually makes the church, serving as an efficacious channel of grace through which the people are transformed into the body of Christ. The divine liturgy, with the Eucharist at its center, is a kind of re-enactment wherein the people of God place themselves in the right posture and enter willingly into the economy of Grace – becoming what God has called them to be – a true leitourgia. The word leitourgia just means “work [service] of the people,” so liturgical worship is worship wherein the people reenact and recall their place in the drama of salvation. Every Eucharistic liturgy is a dramatic re-enactment of the drama of salvation.

Although Schmemann is surely correct that Western theology has often been far too focused on the elements themselves apart from the broader liturgical context, this is not necessarily an indictment of the doctrine of transubstantiation, properly understood. As I’ve already mentioned, transubstantiation was, for Thomas Aquinas, a way of articulating the nature of the Eucharist in liturgical context – not in isolation. Aquinas had no interest in reformation debates about real presence, and to treat his doctrine from within the context of those debates is to engage in an anachronistic exercise, which I do not recommend.

The doctrine of transubstantiation, as we all know, suggests that with the words of institution, the bread and wine are consecrated and become, truly, the body and blood of Jesus Christ. However, Roman Catholics, using Aristotelian language, say that the change is “substantial” and not “accidental.” This, by the way, is key. If we misunderstand the meaning of substance and accident, we cannot possibly understand what Aquinas meant with the doctrine of transubstantiation. In my experience, few protestant theologians understand these distinctions well enough.

So, at the celebration of the Eucharist, after the consecration of the bread, the host will continue to smell, taste, look, and feel like bread because these qualities – taste, feel, appearance – are accidental qualities. However, the substance of the bread – what it really is – its true nature, has been changed into the body of Christ. Frank Beckwith has a simple way of explaining transubstantiation, which I’ve adapted a bit here.

Imagine a carpenter making a desk. That carpenter goes out into the forest and finds an oak tree. We might say that the bare oak wood – with its texture, look, and feel – constitutes the accidental qualities of the tree. The substance of the thing, however, is oak tree. Upon cutting down this tree and using its wood to create a desk, the accidental qualities remain. We still have oak wood. However, we would never say, upon looking at a desk made of oak – “what a beautiful oak tree!” This is because the substance of the thing has been changed. This is no longer a tree but a desk, and the carpenter’s actions – getting up in the morning, gathering his tools, heading out to the woods, cutting down the tree, fashioning a desk – these actions are like a liturgy whose purpose was to transform an Oak Tree into a desk. A friend and former Baptist theologian (who recently crossed the Tiber) named Aaron James explains it this way:

…Substance for the ancients was ‘naturally oriented toward action, hence toward relations of giving-receiving to all around it.’ In contrast to Locke, rather than a static, unknowable substrate, substance was ‘oriented toward self-expressive action.’ And in contrast to Hume, substance was a ‘metaphysical co-principle’ not a separably existent thing.[11]

In other words, substance for Aquinas names the identity of a “thing in relationship” – a thing in relation to its telos or ultimate end. I often hear Protestant pastors and theologians decry transubstantiation because the resurrected body of Christ has ascended to heaven and cannot also be bodily present in the bread and wine. In other words, Protestants think that transubstantiation teaches that Christ is “materially” present in the Eucharist. This is a misunderstanding, however, since substance does not refer to materiality. Substance is a philosophical term describing a signified and truly transcendent nature – not a material nature. The term accident describes the material reality, and Catholics don’t believe that the accidental properties of the host have been turned into Christ’s body, despite common misconceptions.

Edward Schillebeeckx writes that “the essence of a sacrament lies therefore neither in its spiritual significance on the one hand nor in its outward shape on the other, but rather in the manifested signification.”[12] A sacrament is ultimately defined by what it signifies and what it accomplishes. The elements, in other words, may be called corpus verum – truly the body of Christ – only because the Eucharist, within the context of the whole liturgy, is efficacious. The Eucharist is a means by which God transforms his people into Christ’s body – The Eucharist makes the Church – that is a classic and oft-repeated phrase in the western tradition.

With regard to the real presence of Christ in the host, with the words of consecration, the elements are received into the dynamic of the Eucharistic liturgy where the Church is made into the corpus Christi verum. The substance of the host is necessarily related to what it becomes or what it is in the context of a series of relationships. And in the context of the liturgy, transubstantiation insists that we affirm a real presence in the host only in relation to the historical Christ, the re-presented sacrificial lamb Christ, and the fullness of Christ that the Church is in process of becoming.

In this way, the doctrine of transubstantiation constitutes a consistent development – rather than a rupture – with the church’s classic embrace of Eucharistic realism within the context of the liturgical celebration. With the doctrine of transubstantiation, properly understood, Eucharistic realism is firmly connected to the Triune economy of grace and its re-presentation in the Mass. The doctrine of transubstantiation also prohibits us from conceiving of grace as some kind of immaterial or spiritual force that God sends as though over some empty space. Transubstantiation absolutely requires that we look for God’s grace to be mediated through the created order – through our encounter with saints and sinners, through our fellowship with other believers – and especially in the material forms of Word and sacrament.

As an aside, I am an evangelical Anglican and agree completely with the English Reformers who believed that late medieval eucharistic practice, and especially its emphasis on “adoration of the host,” represented an egregious error. I subscribe fully to Articles 28-31 of the 39 Articles. My contention is that Eucharistic doctrine developed improperly with the emergence of philosophical nominalism. I explain this contention more completely in the video below.

I mention all of this as a way to propose that the doctrine of scripture is long overdue for a development like the doctrine of transubstantiation, as originally conceived. Interestingly, although the Church Fathers described both Word and Sacrament in similarly realist terms, a doctrinal development analogous to transubstantiation – ensuring that the Sacred Page would be permanently tethered to and understood from within the context of the Triune economy of grace – has never occurred.

If you find the argument hard to follow, this is what I mean. The Fathers of the Church believed that Jesus Christ is truly present in the Eucharist. Thomas Aquinas believed the same thing and engaged the philosophical milieu of his time (Aristoteleanism) to explain and substantiate what Christians had always believed. Moreover, he did so in a highly sophisticated way that incorporated eucharistic doctrine into a truly synthetic relationship with all other doctrines and situated the whole synthetic matrix in the biblical drama of salvation re-enacted in the liturgy.

The Sacramental Word in the Theological Tradition

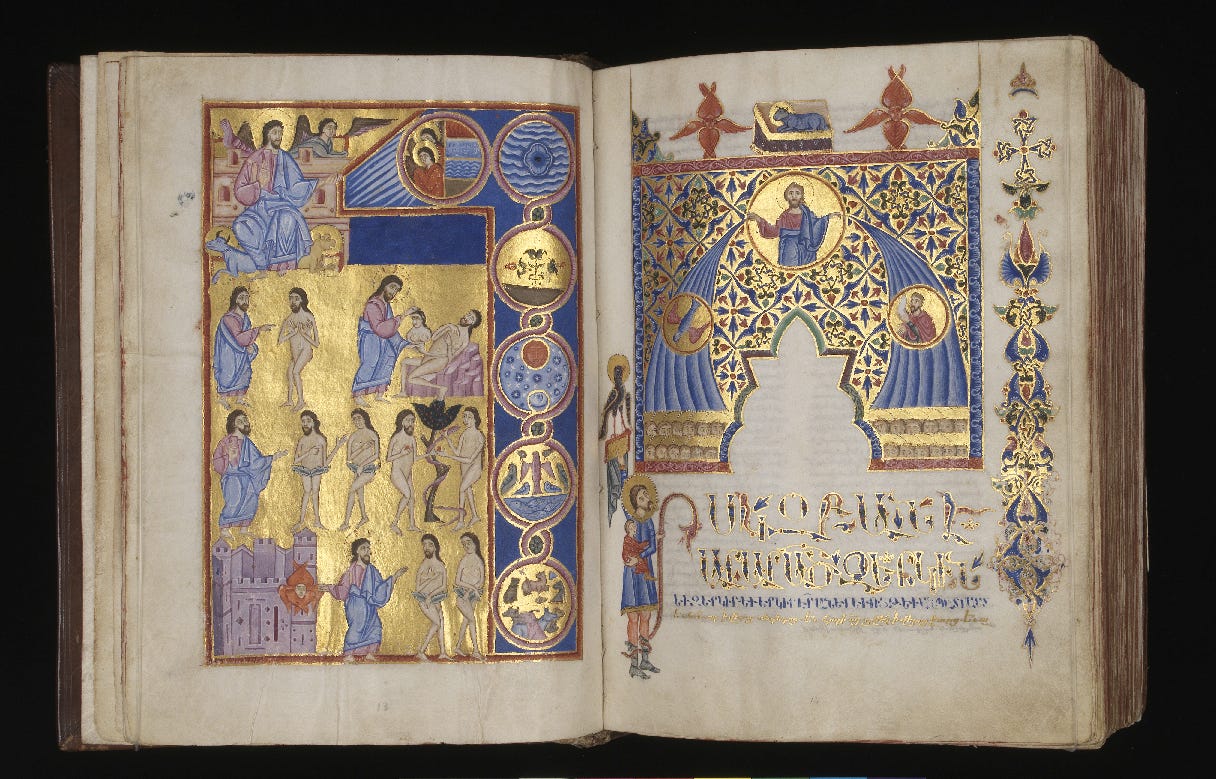

Yet, Sacred Scripture (the bible) was described by the Church fathers using the same realist language used to describe the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. I’ll offer just a few representative quotations, but before I do we should be mindful of the fact that both the “chalice” and the “book” are identified by the early Christian community as the New Covenant or the New Testament. F.X. Durwell explains that

In Christian worship, Holy Scripture is forever linked with that supreme sacrament of Christ’s body and the redemption, the Eucharist; the same name is used for both: ‘This Chalice,’ Our Lord said, ‘is the New Testament’; this book also we call the new Testament; chalice and book, each in its own way, contain the New Covenant, the mystery of our redemption in Christ.[13]

Ignatius of Antioch, on his way to persecution, writes that he finds comfort by “taking refuge in the “Gospel,” as in Jesus’ flesh.”[14] Athanasius declares that “the Lord Himself is in the words of Scripture.”[15] Likewise, Jerome writes: “We have in this world only this one good thing: to feed upon his flesh and drink his blood, not only in the sacrament, but in the reading of Scripture.”[16] It is no exaggeration to say that, for the early church, the real presence of Christ is found in the formal sacraments and in the sacred page in precisely the same way. And because the N.T. canon was not yet fully clarified, Eucharistic realism, which was affirmed by all, provided a grammar for describing the efficacy of sacred scripture, not the other way around.

The classic tradition is reliable in its affirmation that, in Word and Sacrament, Christ is truly present. Indeed the two have always been said to co-inhere, since the sacraments require the Word for their efficacy – there is no consecration without the Word – and the Word requires the sacraments for its fulfillment – Baptism and Eucharist are our true and necessary response to the promise of God’s Word. John Calvin develops this theme in some depth in Book IV of the Institutes, and many Protestants including Baptists like Charles Spurgeon, have followed his lead in referring to the bible as the Sacramental Word.

Arrested Development

So what is the point of all of this? Well, as already noted, it was in response to a denial of Eucharistic realism that a much more robust theory of the real presence in the Eucharist was developed using the language of Aristotealean metaphysics. Remember, doctrines develop when they need to – when some heresy arises that requires careful response from Christians. So… with regard to the Word of God a heresy like the denial of the real presence in the Eucharist (to which Thomas Aquinas responded with his doctrine of Transubstantiation) did not come until perhaps the 18th and 19th centuries with the flowering of historical critical exegetical methods. It was in the 18th and 19th centuries, especially, when scholars launched a truly misguided attack on the veracity of the Bible.

Thus, when theologians turned their attention to a defense of Sacred Scripture and the development of a doctrine of scripture, a radically different philosophical milieu had taken hold of Christendom – the European enlightenment. Accordingly when modern theologians engaged in the development of a doctrine of scripture they were handicapped by the metaphysical developments of the early enlightenment era and especially by a univocal understanding of the relationship between God and man and a referential theory of meaning in relation to the Bible and Truth. In other words (and this is the heart of my thesis) the modern doctrine of scripture developed within a metaphysical and philosophical context that could not be reconciled with Christian truth so easily. There has been a great deal written about this, actually, so I’ll keep my points very brief and merely suggestive.

For example, if Christians work within the context of philosophical nominalism and univocalism – we lose a participatory ontology and a theology of grace as sacramentally and materially mediated (as in Rublev’s famous icon) – we no longer participate in God, receiving his gifts from within the created order. On the contrary God becomes merely one being among others, though of greater power and proportion (as in Monty Python’s Holy Grail).

We relate to this God in a kind of zero-sum game – and we look for his grace to be given over an empty space. This is the way of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism, which has replaced Christianity for too many in our time. Moreover, we come to know this Divine Being as we might know other beings – by learning things about him. Thus, the bible is conceived as a relatively static body of knowledge that has been inspired by God. It contains no errors in its description of God and God’s work. Its meaning is clear, and this static, perfect, clear body of knowledge is entirely necessary for those hoping to know God in order to receive his grace. This is what I mean by a referential theory of meaning – biblical words correspond perfectly with the reality of God. We can know God univocally.

Unfortunately, when we conceive of biblical revelation with a referential theory of meaning, then the bible becomes superfluous to those who have mastered its contents. If we already know all of the key teachings, why return to the bible over and over again? Although we are unlikely to find Christians willing to say that the bible could ever become superflous, many evangelical churches have become what we might call “post-biblical” in their Sunday gatherings. If such a suggestion seems perplexing, I’ve written more here.

Yet, the epistemology associated with a referential theory of meaning is entirely foreign to the bible’s own epistemological outlook. In a recent collection of essays titled The Bible and Epistemology, Mary Healy, Robin Perry, and a variety of biblical scholars and theologians all come to the same conclusion, which is that the knowledge of God is necessarily participatory and can only be received as a gift by the person whose mind and will are conformed to God in Christ. Such knowledge ―does not arise through domination or mastery but through sustained attentiveness to the object. Such attentiveness conforms the knower to what is known rather than the other way around. To acquire knowledge of God, in other words, persons must undergo a transformation of their own intellect and will – they must be conformed to God in Christ.

To use Thomist language, ― all [knowledge of God] is produced by an assimilation of the knower to the thing known, so that assimilation is said to be the cause of knowledge.’[17] Because of who God is, we can never know him through a kind of intellectual mastery, which means that a bible providing intellectual mastery can’t do us much good. Rather, we know God the Father as we are assimilated into the body of his Son through the power of his Spirit by the material means of Word and Sacrament.

Conclusion

As I begin to wrap things up, I’d like to simply reaffirm my contention that the doctrine of scripture is ripe for development using the language of sacrament, which tethers it to the economy of grace materially re-presented in the liturgy.[18]

Now, it is well known that doctrines are hermeneutical in nature. They establish the rules of sound biblical interpretation, and they protect us from idolatry. Protestantism is a chaotic mess at the moment, and the Biblicism of so many protestant evangelicals, which has developed in an inadequate metaphysical and philosophical context, has allowed the bible to be un-tethered from the church’s rich sacramental and liturgical heritage. Somehow, we have moved from worship where the words of scripture continually mediate our entry into the Word, to contemporary worship services that imagine an unmediated encounter with God that neglects the means of grace without which such an encounter is entirely non-nonsensical.

With a more developed doctrine of the sacramental word, we could talk about the canonical process, where inspired texts used in liturgical assemblies become Sacred Scripture, as akin to a process of consecration. These material texts are now Holy Objects, which bring us into the presence of Christ, and they should be read and used in a manner consistent with their own sacramental nature.

Moreover, a more robust doctrine of the sacramental Word, will help to clarify and solidify the church’s traditional handling of scripture in the gathered assembly (think of the procession of the gospel and the kissing of the book) and require that the liturgical assembly remains the gravitational center of individual piety, as it once was for all Christians.

A more developed doctrine of the sacramental Word, could, at least in theory, give us a sharper tool for weeding out quite a bit of nonsense so that we can pass on a faith less defiled to the next generation.

***Incidentally, since writing this essay, I’ve come to realize that C.S. Lewis is work called transpositions is making a very similar argument to the one that I make here. I’ve explored that idea in a podcast interview that you can access here.

[1] Within both Roman Catholic and Orthodox theology, it is much more common to find a treatment of scripture from within the context of salvation history/the economy of salvation. Building on Vatican II’s Dei Verbum and an earlier generation of Roman Catholic scholars such as Henri de Lubac, the work of Scott Hahn in Roman Catholic theology is a contemporary expression of a very thoughtful approach. For a notable exception in protestant theology see John Webster, Holy Scripture: A Dogmatic Sketch, Current Issues in Theology (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

[2]Jean Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, trans. Beveridge, Henry (Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans, 1981), 4.14.4.

[3] Michael Horton, The Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology for Pilgrims on the Way (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2011), 751ff.

[4] F.-X. Durrwell, The Eucharist: Presence of Christ, Dimension Library of Living Catholic Thought, 10 (Denville, N.J: Dimension Books, 1974).

[5] “Holy Spirit Interactive: Scott Hahn – Scripture Is Sacramental,” accessed March 15, 2013, http://www.holyspiritinteractive.net/columns/guests/scotthahn/scripture.asp.

[6] For the classic treatment of the development of the doctrine of transubstantiation, see Henri de Lubac, Corpus Mysticum: The Eucharist and the Church in the Middle Ages, trans. Simmonds, Gemma (London: SCM, 2006).

[7] J. N. D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, 3d ed (London: A. & C. Black, 1965), 440.

[8] For more on this issue, see Bryan C. Hollon, “Sacramental Realism and the Powers: A Reconsideration of de Lubac’s Eucharistic Ecclesiology,” Ashland Theological Journal (2011): 21–32.

[9] Schmemann, For the Life of the World: Sacraments and Orthodoxy, 26.

[10] Schmemann, For the Life of the World: Sacraments and Orthodoxy, 34.

[11] Aaron James, “Eucharistic Identity and Analogous Uses of Language,” Unpublished Conference Presentation: Young Scholars in the Baptist Academy (Honolulu, Hawaii, July 2010), 18.

[12] Ibid., 96.

[13] Ibid., 40–41.

[14] Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Philadelphians, 5.1.

[15] Athanasius of Alexandria, Letter to Marcellinus, 33.

[16] Jerome, Commentary on Ecclesiastes, cited in Francois-Xavier, CSSR Durwell, “The Sacrament of Scripture,” 45.

[17] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, I, q. 12, a. 9. Cited in Mary Healy and Robin Parry, The Bible and Epistemology Biblical Soundings on the Knowledge of God (Milton Keynes, U.K.: Paternoster, 2007). See also my article, Knowledge of God as Assimilation and Participation.

[18] I’ve not addressed John Webster’s wonderful book (with which I agree almost entirely) titled Holy Scripture: A Dogmatic Sketch, but this is where I think Webster needs to go further– he fails to use sacramental and liturgical language, which ensure that we look for the mediation of God’s grace in material things.

[19] Any study of late medieval religion must begin with the liturgy, for within that great seasonal cycle of fast and festival, of ritual observance and symbolic gesture, lay Christians found the paradigms and the stories which shaped their perception of the world and their place within it. Within the liturgy birth, copulation, and death, journeying and homecoming, guilt and forgiveness, the blessing of homely things and the call to pass beyond them were all located, tested, and sanctioned. In the liturgy and in the sacramental celebrations which were its central moments, medieval people found the key to the meaning and purpose of their lives…the liturgy functioned at a variety of levels, offering spectacle, instruction, and a communal context for the affective piety which sought even in the formalized action of the Mass and its attendant ceremonies a stimulus to individual devotion. Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, C.1400-c.1580 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992), 11.