Several years ago, I taught an honors theology class at the undergraduate level and had my students conduct a research project, as one of their course assignments. We broke students into groups of four and sent them into churches of their own choosing in order to examine biblical content in worship services. All of the groups chose to attend services at large, contemporary churches, which are quite typical (in terms of worship culture) of christian churches across the country.

The students took recording devices and produced complete transcripts of the services. Then, they produced reports describing both the quantity of scripture and the way that scripture was used in hymns, praise choruses, readings, sermons, etc. They asked questions such as: was the bible presented in long sections or in bits and pieces? Was scripture read in context, and did the various passages read in the service have an obvious thematic coherence?

Suffice it to say, the results were troubling, but not surprising. There was very little scripture read or sung at all, and the scripture that was incorporated into sermons was usually, though not in every instance, piecemeal. In none of the churches were there any long readings from scripture. Not one church coupled readings of Old Testament promise with New Testament fulfillment. There were no responsive readings, no psalms sung, no canticles, no confessions of sin using the words of scripture, no communal recitation of the Lord’s Prayer, no confessions of faith or creeds offering a kind of summation of biblical theology. All of the churches were non-sacramental, though one church did have communion – but without a reading from the biblical words of institution or any other formal preparation. Cups of grape juice and crackers were simply placed on tables scattered about the worship space, and those who understood what was happening went to the tables and helped themselves as the band played a song.

Regarding the music that these students encountered, most of the songs were dominated by highly subjective lyrics – focused more on us, our feelings, and our pursuit of God than on God and God’s goodness, work on our behalf, and Glory. The worshipers spent most of the service telling God how much they love him and how sincerely they were going to worship and serve him.

Indeed, the presupposition underlying so much contemporary worship seems to be pelagian. That is, the idea that our efforts reconcile us to God seems to saturate contemporary worship, rendering it little more than a kind of communal catharsis and therefore, hopeless. We are not reconciled to God because of our love for God. Instead, our hope is grounded in God’s prior love and action. True Christian worship should always get this theme right if it wants to avoid getting the gospel wrong.

Lyrics describing God’s nature and character, God’s love for us, and God’s sacrificial work on our behalf were hardly evident in the worship songs. The “good deposit” that Paul speaks of – the rich kerygma that Paul preached in the book of Acts – was hard to find in these services. On the whole, the congregation’s role in the service was passive. It involved sitting and listening, singing along during the praise choruses but not consistently and not with a great deal of enthusiasm. The atmosphere was far more like a rock concert than a traditional Christians worship service. And this was true of every church the students visited. One church actually employed smoke machines during the praise sets, replicating a rock concert as much as possible.

It is noteworthy that these services were almost entirely non-participatory. The people in the churches were expected to do almost nothing. They sat or stood before a stage and watched the show – that about sums it up. As I listened to my students present their findings, I couldn’t help but think how odd this would be to the 16th century protestant reformers who so adamantly insisted, at a time when the laity was largely cut off from participation in the mass, that worship services must truly be the “work of the people” (this is the definition of liturgy, by the way. Liturgy means “work of the people”).

I also found myself reflecting on how different the situation is in more liturgical traditions today. Indeed, my family worshiped in a Roman Catholic church on Palm Sunday of that year, and the readings from scripture, which included the people in regular response, were so long that it was difficult to stand all the way through. Many of the elderly had to sit. The Roman Catholic mass, much like the Orthodox and Anglican liturgies, is little more than the bible itself arranged for prayer and worship. Although, I must say, the Anglican Book of Common Prayer incorporates the Bible in its liturgies in a purer and less diluted fashion than other traditions do. The Book of Common Prayer is truly the Bible itself arranged for prayer and worship.

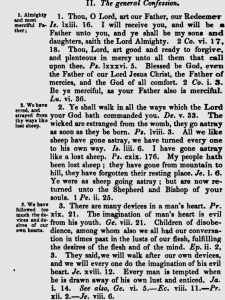

Consider the illustration above. This is from a 19th century text titled, The Liturgy Compared with the Bible. The numbered sentences on the left come directly from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. The longer paragraphs on the right are taken directly from the biblical passages that are either quoted or paraphrased in the Book of Common Prayer. This text covers the entire prayer book, showing how morning prayer, evening prayer, eucharistic liturgies, ordination liturgies, baptismal liturgies, etc. are completely saturated with Sacred Scripture. To pray and worship using these time-tested liturgies is simply to pray God’s Word back to God, letting the Word of God mediate our relationship with the Father, through the power of the Holy Spirit. This is sound theology informing worship.

Traditional liturgy assumes that we can never move beyond the bible as though we do not need it anymore. Rather, the bible continually mediates God’s saving presence to us, so we want to make sure that our hymns, sermons, prayers, etc. enflesh the people of God within the Word of God.

Jesus Christ, the Word Made Flesh, is the one mediator between God and Man, so to worship without the mediation of God’s own Word is simply unchristian.

God is not one being among many, though of greater power and proportion. There is no empty space that divides us from God so that our worship and prayer are meant to bridge this empty space. Rather, we Christians worship the one true God in whom we live and move and have our being. This God has entered into our world, taking on flesh and leaving us with material means of grace. We find this God in our midst, and our part is to enter into the work on earth that he is already doing. The Bible is one of numerous “means of grace” to use the language of John Wesley, and the entire christian tradition that preceded him holds this perspective. It is a strange and unprecedented development to see Christians supposedly worshiping God and doing so without the mediation of God’s Word. This problem goes far beyond any debate about the relative merit or lack of merit in praise choruses. It is a problem of a participatory vs. a non-participatory understanding of human nature in relation to God. Classical Trinitarianism (participatory) vs. nominalism (non-participatory). Much contemporary worship seems to be nominalist at its core.

The Liturgy Compared with the Bible makes a very dramatic illustration of just how truly “biblical” the church’s traditional liturgies are. I have heard people suggest that liturgy is not biblical because it is not clearly prescribed in the New Testament. Such a claim seems absurd when considering the sheer quantity of scripture found in liturgical services when compared with most contemporary services. If we attend a service characterized by a set of three or four largely subjective praise choruses followed by a thematic sermon and concluding with one or two more praise choruses, then we have certainly not worshiped in a way that is biblical in any meaningful sense.

It seems clear to me that contemporary evangelicalism has already entered into an era that may be righty described as “post-biblical protestantism,” and we should be concerned.

Clearly, there is much more to a church than the Sunday service. There are small groups, bible studies, mission trips, accountability groups, and much, much more. But we should not underestimate the formative power of communal worship; nor should we forget that God desires our worship and that he has provided His eternal Word as a means to facilitate it. Christians of almost all former generations understood this truth. Someone once said, “Let me write the hymns and the music of the church, and I care very little who writes the theology.” No doubt, a church’s worship speaks volumes about its basic understanding of God and all else in light of God. What do our post-biblical services suggest about the state of contemporary evangelical christianity?

Why It Matters

Here is my concern. Study after study has demonstrated that contemporary evangelical Christians – and especially young people (13-29) do not understand even the most basic truths of the Christian faith. In a very famous book published in the year 2,000, Christian Smith and Melissa Lundquist interviewed over 3,000 teenagers, churchgoing evangelical teens, and found that they believed little more than this:

“A god exists who created and ordered the world and watches over human life on earth.”

“God wants people to be good, nice, and fair to each other, as taught in the Bible and by most world religions.“

“The central goal of life is to be happy and to feel good about oneself.”

“God does not need to be particularly involved in one’s life except when God is needed to resolve a problem.”

“Good people go to heaven when they die.”

Smith and Lundquist coined a phrase to describe this growing religious sensibility. They call it “moralistic therapeutic deism.” It is not Christianity, to be sure. Don’t miss the point here – many of those high-energy youth programs are really good at producing deists – Christians, not so much.

Going hand in hand with this trend, other studies suggest that American evangelicals are facing a serious crisis of biblical illiteracy. Evangelical Christians revere the Bible, but very few, and especially the young, actually attend to it and know it deeply. If we actually believe, as we claim to believe, that reading the Bible brings us into the presence of God’s living Word, then this trend is clearly a major problem. Surely, it calls for a major course correction in non-sacramental and non-liturgical evangelical churches.

The future of evangelical christianity, though it may take many years and very substantial numerical decline, must be a return to the substance of traditional, liturgical worship working symbiotically with classic, creedal, and confessional faith.