This session is part of the multi-post Study Guide titled "Learning to Pray with C.S. Lewis." You may find it helpful to refer to the introduction and session one to understand the nature of the project as a whole. There will be 10 sessions in all.

"We shall be with Christ, we shall be like Him, we shall have glory..." - C.S. Lewis, Letters to Malcolm

Primary Readings:

Letters to Malcolm, Letter 22

C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, Book 4, Chapters 10-11: "Nice People or New Men" and "The New Men"

Theological Context: Beyond Nature to Glory

In the final letter of Letters to Malcolm and the opening chapters of Miracles, Lewis addresses the fundamental ontological question at the heart of prayer: Is reality ultimately natural or supernatural? This question transcends mere academic speculation, touching the very foundation of prayer's meaning and efficacy. If reality is purely material, prayer becomes at best psychological self-adjustment and at worst elaborate self-deception. If reality includes genuine supernatural dimensions, prayer becomes meaningful communion with transcendent reality.

Lewis confronts naturalism—"the doctrine that only Nature—the whole interlocked system—exists"—with a philosophically rigorous defense of supernaturalism. This defense provides the essential foundation for any coherent understanding of prayer, which necessarily presupposes reality beyond the material. What distinguishes Lewis's approach is his insistence that supernatural reality can be rationally defended. In Mere Christianity, he presents the culmination of this vision:

"He will make the feeblest and filthiest of us into a god or goddess, a dazzling, radiant, immortal creature."

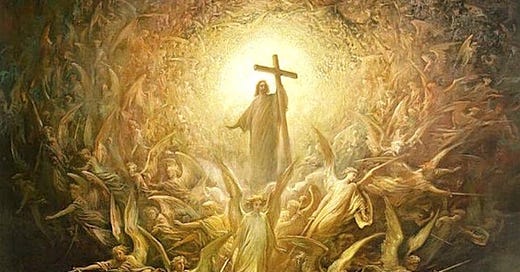

Prayer in this sense is participation in humanity's supernatural development—becoming through grace what Christ is by nature. As Lewis notes, "The Next Step has already appeared"—and prayer invites us to join this transformation where "God is going to invade... When the author walks onto the stage the play is over."

Key Concepts

1. Naturalism vs. Supernaturalism: The Foundation of Prayer

Lewis begins Miracles by establishing a crucial distinction: "Some people believe that nothing exists except Nature; I call these people Naturalists. Others think that, besides Nature, there exists something else; I call them Supernaturalists" (chapter 2). This distinction isn't merely academic—it determines whether prayer has any meaning beyond psychological exercise.

For naturalists, prayer can only be a psychological phenomenon within the "total system" of nature. By contrast, Lewis defends supernaturalism on rational grounds, arguing that naturalism contradicts itself:

"If the solar system was brought about by an accidental collision, then the appearance of organic life on this planet was also an accident... If so, then all our present thoughts are mere accidents" (chapter 3).

This includes the thought that naturalism is true. The essential insight is that rational thought itself points beyond nature to a supernatural source. As Lewis quotes from Professor J.B.S. Haldane:

"If my mental processes are determined wholly by the motions of atoms in my brain, I have no reason to suppose that my beliefs are true."

As Lewis writes in chapter 5 of Miracles:

'Human minds, then, are not the only supernatural entities that exist. They do not come from nowhere. Each has come into Nature from Supernature: each has its tap-root in an eternal, self-existent, rational Being, whom we call God.'

Prayer, in this light, represents the natural communication or “transposition” between a mind and its ultimate Source.

2. The Relationship Between Nature and Supernature

Lewis articulates a nuanced understanding of how nature and supernature relate. Rather than imagining the supernatural as simply another layer in the universe—"a higher floor in the same building"—he presents it as the ground of nature's existence:

"In relation to Nature, Rational thought goes on 'of its own accord' or exists 'on its own.' It does not follow that rational thought exists absolutely on its own. It might be dependent on something else" (ch. 4).

Lewis thus imagines prayer not as reaching up to a distant supernatural realm but as participating in the supernatural reality that already grounds our rational existence. Lewis further develops this through his concept of "transposition"—how higher realities manifest in lower mediums. In Mere Christianity, Lewis offers a vivid metaphor for this relationship:

"Imagine turning a tin soldier into a real little man. It would involve turning the tin into flesh. And suppose the tin soldier did not like it... He thinks you are killing him."

This analogy reveals why prayer so often involves struggle—we resist the transformation we most deeply need.

3. The Challenge to Liberal Christianity

In Letter 22, Lewis critiques liberal Christianity's attempt to preserve religious forms while emptying them of supernatural content:

"They genuinely believe that writers of my sort are doing a great deal of harm. They themselves find it impossible to accept most of the articles of the 'faith once given to the saints.' They are nevertheless extremely anxious that some vestigial religion which they (not we) can describe as 'Christianity' should continue to exist" (Letter 22).

Lewis argues that removing supernatural elements to make Christianity more "credible" produces something neither intellectually compelling nor spiritually satisfying. This affects prayer directly—if stripped of its supernatural dimension, prayer becomes merely psychological exercise rather than genuine communion with God. In Mere Christianity, Lewis cuts to the heart of this issue:

"The question is not what we intended ourselves to be, but what He intended us to be when He made us... It is the difference between paint which is merely laid on the surface, and a dye or stain which soaks right through."

Authentic prayer involves radical openness to supernatural transformation rather than surface-level behavioral adjustments.

4. Resurrection and Eschatological Hope

Lewis concludes Letters to Malcolm with reflections on bodily resurrection that reframe both materialistic and spiritualized misunderstandings:

"We are not, in this doctrine, concerned with matter as such at all: with waves and atoms and all that. What the soul cries out for is the resurrection of the senses. Even in this life matter would be nothing to us if it were not the source of sensations" (Letter 22).

Rather than reassembling physical atoms, Lewis suggests resurrection involves the transfiguration of sensory experience. Our present experiences offer glimpses of this future reality:

"We have already a feeble and intermittent power of raising dead sensations from their graves. I mean, of course, memory" (Letter 22).

Perhaps his most striking insight concerns resurrection's communal dimension:

"I can now communicate to you the vanished fields of my boyhood—they are building-estates today—only imperfectly by words. Perhaps the day is coming when I can take you for a walk through them" (Letter 22).

In Mere Christianity, Lewis captures the cosmic significance of this hope:

"God is going to invade, all right... This time it will be God without disguise; something so overwhelming that it will strike either irresistible love or irresistible horror into every creature."

Prayer becomes both anticipation of and preparation for this final unveiling of God. As we pray, we participate in what Lewis calls the 'dress rehearsal' for eternal communion. Our moments of petition, adoration, confession, and thanksgiving are not just temporal exercises but participation in the consummation that all creation is moving towards. Each genuine prayer, however humble, serves as what Lewis describes in 'The Weight of Glory' as 'the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited.' In this light, prayer is not primarily about immediate results but about progressive incorporation into the life of Jesus Christ, the one who will be all in all.

Questions for Reflection

How does the distinction between naturalism and supernaturalism affect your approach to prayer? In what ways might recognizing prayer's supernatural foundation shape both expectations and practice?

Lewis argues that rational thought itself cannot be accounted for within a purely naturalistic framework. How does this philosophical defense of the supernatural relate to prayer's rational basis? What implications might this have for addressing contemporary skepticism about prayer?

Lewis suggests in Letter 22 that resurrection involves not the reassembly of physical atoms but the resurrection of sensory experience. How might this conception reshape our understanding of embodied experience now, and what might it suggest about heaven?

Consider Lewis's suggestion that memory offers "a feeble and intermittent power of raising dead sensations from their graves." What experiences in your own life have given you glimpses of what resurrection reality might entail?

Lewis critiques liberal Christianity's attempt to preserve religious forms while emptying them of supernatural content. How might this critique apply to contemporary approaches to prayer that emphasize only psychological benefits? What aspects of prayer necessarily depend on supernatural reality?

Lewis describes human minds as "supernatural entities" with their "tap-root in an eternal, self-existent, rational Being." How might this conception of human nature affect how we understand prayer? What would it mean to pray with awareness of our supernatural nature?

How does Lewis's vision of prayer as participation in divine reality rather than technique for achieving results challenge contemporary approaches to spirituality? What would a prayer life based on relationship rather than technique look like in practice?

Practical Exercise: Integration and Synthesis (2-3 days)

As we conclude our exploration of Letters to Malcolm, this exercise invites integration of key insights into personal prayer practice:

Review previous exercises: Look back through your reflections and notes from previous sessions, identifying 3-5 practices or insights that have been most meaningful for your prayer life.

Create a personal "prayer portrait": Write a brief description (1-2 paragraphs) of what integrated prayer looks like for you, incorporating insights from Lewis that resonate most deeply with your experience and needs.

Develop a balanced practice: Design a sustainable prayer rhythm that incorporates multiple dimensions of prayer discussed throughout Letters to Malcolm:

Adoration—beginning with concrete experiences that point to divine glory

Petition—making specific requests while acknowledging divine wisdom

Confession—honestly acknowledging sin without morbid fixation

Communion—participating in both individual and corporate prayer

Practice resurrection hope: Following Lewis's reflections in Letter 22, spend time each day attending to sensory experiences with awareness of their eternal significance. Consider how seemingly ordinary perceptions might offer glimpses of resurrection reality.

After this period, write a brief reflection on how engagement with Lewis's thought has transformed your understanding and practice of prayer. What aspects of prayer that previously seemed problematic have found new meaning? What practices have become more sustainable or fruitful? How has your vision of prayer's ultimate purpose evolved?