Several years ago, my wife and I gathered a group of people and planted an Anglican church in Canton, Ohio where many Christians are unfamiliar with liturgical forms of worship. Indeed, our church was made up almost entirely of people from non-denominational or free-church backgrounds. I wrote this little essay for that group of people, to serve as a very brief introduction to the “dramatic” nature of the Eucharistic liturgy, found in our 2019 prayerbook. It may also serve as a helpful refresher for those who have worshiped this way for some time.

In my mind, these four characteristics of Anglican worship are especially noteworthy.

First, Anglican worship is not “seeker-sensitive.”

Or perhaps it would be better to say that Anglican worship IS sensitive to the fact that learning to worship is fundamental to growing in Christian faith. In the earliest centuries of the church, only baptized Christians were allowed to participate fully in worship services. Despite this restriction, the church grew at a staggering pace – from perhaps 1,000 Christians at the time of Pentecost to more than 30,000,000 by the early 4th century. This growth occurred during periods of severe persecution. The church evangelized, but it was wise to avoid confusing worship with evangelism. Those who were interested in becoming Christian became “catechumens,” and were asked to study and learn the faith under elders for a period of between 1 and 3 years. It was believed that Christianity is necessarily a learned faith and that God cannot be worshiped in “Spirit and Truth” except by those who have submitted themselves to a discipleship process. How, after all, can we worship God if we do not know who God is? And how can we know who God is if we do not know the biblical history of salvation, which culminates in the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ? As St. Paul reminds us in Romans 10:7, “faith comes from hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ.”

Although Anglican churches do not restrict catechumens from being present in worship (though only baptized Christians may partake of the Eucharist), we share the early church’s conviction that worship in Spirit and Truth requires a process of discipleship. Worship is for Christians and must be learned. Just as we grow in sanctification and prayer, Christians grow in worship. Anglican worship thus becomes deeper, more beautiful, and more meaningful as faith and knowledge increase. Anglican churches should, of necessity, place a great deal of emphasis on teaching the faith, since right worship requires such teaching.

Second, Anglican worship is saturated with the Word of God.

Thomas Cranmer, the first Anglican Archbishop at the time of the reformation, wrote a famous prayer showing his high regard for biblical literacy and devotion:

“BLESSED Lord, who hast caused all holy Scriptures to be written for our learning; Grant that we may in such wise hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them, that by patience and comfort of thy holy Word, we may embrace, and ever hold fast, the blessed hope of everlasting life, which thou hast given us in our Saviour Jesus Christ. Amen.”

Cranmer may have been indebted to the great reformed theologian, John Calvin, who believed that “the Bible is the language of the Holy Spirit” and that there is a necessary relationship between learning the bible deeply and becoming the kinds of Christians within whom the Spirit can work effectively. In Cranmer’s mind, people who “hear, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest” the scriptures become attuned to the voice and will of God, learn the ongoing necessity of confession and repentance, grow in wisdom and discernment, cultivate the gifts of the Spirit, and offer true witness to Jesus Christ.

For this reason, when Thomas Cranmer crafted the first Book of Common Prayer in 1549, his intention was to immerse Christian worshipers in the Word of God so that they might be formed into the kinds of people within whom the Spirit can work. To this day, Anglicans use the Book of Common Prayer in corporate worship and private devotion, since it is little more than the bible itself arranged for prayer and worship.

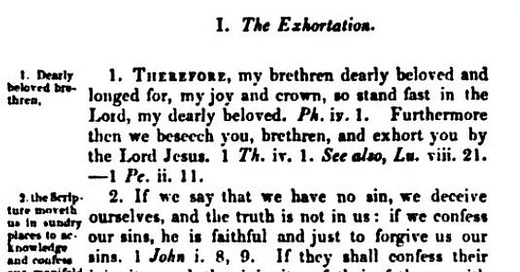

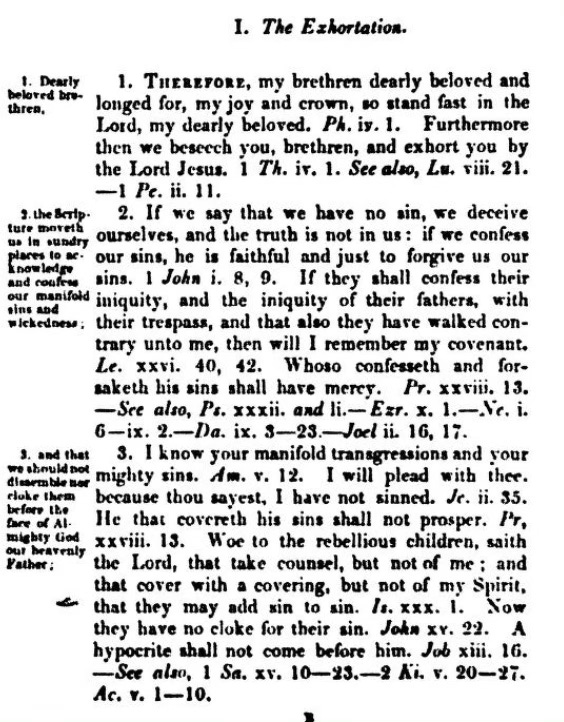

Consider the illustration on the right. This is from a 19th century text titled, The Liturgy Compared with the Bible. The numbered sentences on the left come directly from the morning prayer service in the Book of Common Prayer. The longer paragraphs on the right are taken directly from the biblical passages that are either quoted or paraphrased in the Book of Common Prayer. The Liturgy Compared with the Bible covers the entire prayer book, showing how Morning Prayer, Evening Prayer, Eucharistic liturgies, ordination liturgies, baptismal liturgies, etc. are completely saturated with Sacred Scripture. To pray and worship as Anglican Christians is simply to pray God’s Word back to God, letting the Word of God mediate our relationship with the Father, through the power of the Holy Spirit. This is sound theology informing worship.

Third, Anglican Worship attends to the whole biblical story.

As is well-known, the bible is made up of 66 individual books written at different times by different people. However, it tells one, coherent story of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation. God made us in his own image, we rebelled, and God gathered a people together in order to redeem his fallen world. Redemption was accomplished through Jesus Christ, and we are now awaiting the final consummation of Christ’s work. Traditionally, Christians have worshiped God by simply retelling and re-enacting this story. Consider the Christian liturgical year as explained in the video below.

So, as Anglican and other Christians worship through the liturgical year, they are immersing themselves in the biblical story because they believe that God’s Word will form them in faith, hope, and love. However, Anglicans and other Christians also attend to the whole story of salvation during every Sunday service that involves preaching and sacraments. Indeed, there are four basic parts to the typical Sunday worship service:

The Gathering – The service begins with a hymn and a procession. It includes several prayers, a recitation or summary of the ten commandments, and an ancient hymn such as the Trisagion or the Gloria in Excelsis. This gathering is the way that we put ourselves in the place of the 12 tribes of Israel and the 12 disciples of Christ who were gathered together by God for redemption and witness.

The Word of God – Just like Israel and the disciples of Christ, we are gathered together so that God can address us with his holy Word. At this point in the service, we begin a series of readings from scripture, which includes a lesson from the Old Testament, a Psalm, a New Testament Epistle, and a Gospel. The readings are related to each other thematically in order to communicate the fact that God makes promises and keeps them. The readings, in other words, immerse us in the whole biblical story. Dietrich Bonhoeffer explains what it means to hear God’s Word in this way:

“Consecutive reading of biblical books forces everyone who wants to hear to put himself, or to allow himself to be found, where God has acted once and for all for the salvation of men. We become a part of what once took place for our salvation. Forgetting and loosing ourselves, we, too, pass through the Red Sea, through the desert, across the Jordan into the promised Land. With Israel we fall into doubt and unbelief and through punishment and repentance experience God’s help and faithfulness. All this is not mere reverie but holy, godly reality. We are torn out of our own existence and set down in the midst of the holy history of God on earth.” Bonhoeffer, Life Together, 53

Communion – In the gospels, after Jesus’ disciples learned from his teachings and miracles, they followed him to Jerusalem and ultimately witnessed his Passion. At this point in the service, we do likewise as Christ’s passion is reenacted in the Eucharist. The German reformer, Martin Luther, claimed that a true church exists wherever the Word is rightly preached and the sacraments are rightly administered. For Luther, it is not enough to merely hear the Word of God. Instead, we are asked to respond to God’s Word by giving up ourselves as living sacrifices and entering into the communion of Christ’s body. This is what we are doing when we approach the altar and receive the body and blood of Christ. The Eucharist is our faithful response after hearing God’s word proclaimed. This is our “yes” to the call of Christ to come, take up our crosses, and follow.

Sending – After the resurrection, and once Jesus had explained how the whole of scripture is fulfilled in his own life, death, and resurrection, he sent his followers out to “make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” The service ends as we are sent out to do likewise.

In summary, Anglicans, like Christians all over the world today and throughout history, tell and re-enact the biblical story as we worship through the Christian year and at each weekly gathering. This is among the most important ways that we “hear, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest” holy scripture.

Fourth, Anglican worship requires active participation from the people.

The protestant reformers were scandalized by the fact that, in Roman Catholic churches during the late middle ages, the laity were little more than passive observers in the mass. Priests led in Latin (which most laity did not understand) from the front of the church, and the people observed at a distance, often misunderstanding much of what was happening.

Oddly, evangelical Christian worship is often similar to medieval catholic worship, since the people are passive observers of the “worship” service. The praise band plays from the front, the preacher speaks, and all the while, the audience observes in the way one might observe a concert performance. Certainly, the people would never consider themselves the primary performers in many contemporary Protestant services in our time.

In stark contrast to this passivity, Anglican Christians are active participants in worship. Depending on the traditions of your Anglican parish, you may notice people bowing before the cross during the procession, kneeling for prayer and confession, making the sign of the cross at various points in the liturgy, greeting each other at the passing of the peace, going forward and often kneeling to receive communion, listening to God’s Word and affirming the faith boldly by reciting the creeds, participating verbally during various prayers, reading of the psalms, and much more. Anglican worship involves the people in an active participation in the biblical story in every gathering. This, by the way, is the meaning of the word “liturgy.” From the Greek leitourgia, the word means “the work of the people” and refers specifically to the role that God’s people play in the long history of salvation. Anglican worship is liturgical because it invites the people to dramatically re-enact their role in God’s story of redemption, as Bonhoeffer explains in the quotation above from Life Together.

I could say much more, of course, but let me conclude by paraphrasing Bonhoeffer again, since he insists that Christian worship must always serve the Word of God. This is exactly what a good liturgical worship service will do – it will draw us into God’s Word, and over time, plant God’s Word inside of us.